The enablers of Abu Dhabi’s outcomes-focused vision for the future

Posted:

17 Feb 2023, 5 p.m.

Author:

-

Chih Hoong Sin

Expert Advisor, Social Outcomes and Social Investment

Chih Hoong Sin

Expert Advisor, Social Outcomes and Social Investment

Topics:

Outcomes-based approaches

In this blog, Dr Chih Hoong Sin shares the journey of stakeholders in Abu Dhabi and explores how individual projects and workstreams, while having specific objectives, are nonetheless orchestrated to feed into an ecosystem-building aim.

In this blog, Dr Chih Hoong Sin shares the journey of stakeholders in Abu Dhabi and explores how individual projects and workstreams, while having specific objectives, are nonetheless orchestrated to feed into an ecosystem-building aim.

Growing for a sustainable future

The Emirate of Abu Dhabi has long recognised the need for a diversified economy driven by thriving private and social sector players. In parallel, the Abu Dhabi Government has identified that social and economic development should go hand in hand. This has led to a desire to foster community-led and impact-driven development. However, as the Inclusive Economy experience of the United Kingdom has demonstrated, creating the conditions that trigger and sustain a virtuous cycle of cross-sector and civil society partnerships is not straightforward.

Re-orientating investment

There is concerted effort to complement established social protection and welfare practices in Abu Dhabi with a social investment approach. In this instance, social investment has a broader implication than the conventional financial usage of the term. The Government of Abu Dhabi seeks to invest in the conditions that optimise human capital, activating citizens, civil society organisations and the private sector into engaged and proactive contributors to economic and social development.

This ambitious vision requires a compelling case for change to be made, with a number of programmes seeking to model new behaviours and ways of working. Social Impact Bonds (SIBs), for example, have become a standard-bearer of this commitment. Stakeholders in Abu Dhabi, however, have a wider objective for SIBs – viewing them as a way of familiarising ecosystem players with key characteristics of a social investment paradigm, including the activation of non-public sector capacities and resources towards the most pressing social needs. The agenda is driven by a single public agency, the Authority of Social Contribution - Ma’an, which also has a mandate to facilitate public, private and ‘third’ sector collaboration and investment to build a culture of social contribution and participation in the Emirate. As such, SIBs are part of a wider and holistic array of approaches that Ma’an has at its disposal to stimulate impact-driven development.

The adoption of SIBs, therefore, can be understood from this wider perspective. For instance, as a result of investing in the Atmah SIB – the first in Abu Dhabi and the wider Gulf region – Al Dar Properties experienced first-hand the transparency and evidence-based problem-solving approach involving cross-sector collaboration. The overarching system-level objectives underpinning the Atmah SIB meant that governance structures were set up to involve strategic partners (not just project delivery partners), and specific attention was paid to the extraction of system-level learning for key partners over and above the operational aspects of the SIB.

For investors, the governance and learning structures of the Atmah SIB did not merely look at performance metrics, but also actively socialised them into the wider potential and opportunities of ‘investing in social good’, over and above the conventional ‘giving’ paradigm that dominates in the region. This has provoked a mindset change in private sector partners; encouraging them to explore other ways of embedding outcomes-focused approaches within their own corporations as well as becoming champions for social investment more widely.

Ecosystem-building is not straightforward. Distinct narratives were needed for different stakeholder groups in a way that makes sense to the local context. Continued effort is required, for instance, in persuading local investors to think and act beyond the deeply entrenched ‘giving’ paradigm. Ma’an has aligned social investment with the widely accepted ‘doing good’ mentality, while at the same time distinguishing it from conventional giving through the language of ‘doing good better’.

In addition, pipeline generation will be vital as suppliers of social finance in Abu Dhabi and elsewhere often speak of their interest in scale and continuity. Careful expectation management alongside strategic development of the ecosystem to generate sufficient demand-side pull for social investment will be a priority over the coming years.

Other forms of activation

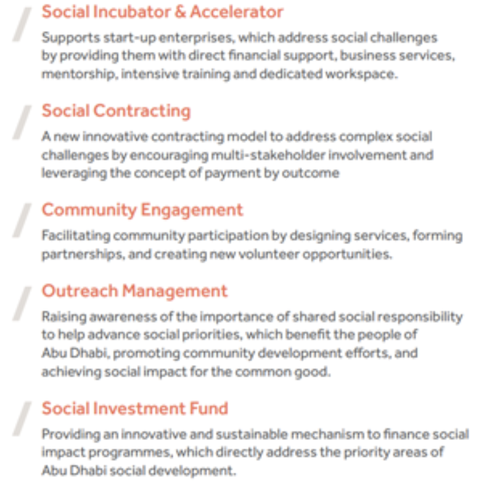

Social contracting is one of five pillars of activity through which Ma’an has been supporting and contributing to the social value agenda (see Figure 1).

Each of these pillars contributes towards the ecosystem-building goal. For example, the Ma’an Social Incubator & Accelerator (MSI) pillar plays an important role in incubating and accelerating non-profit entities and social enterprises that are aligned to the strategic social priorities identified by the Government. Community Engagement (CE), meanwhile, has recruited and sustained a growing network of volunteers through community activities designed to tie in with one or more of the Government’s key social priorities.

More importantly, beyond the contribution of individual pillars, Ma’an has sought to leverage the interaction amongst these pillars in order to amplify collective impact. For example, as I have described in a previous blog, the MSI pillar attempts to overcome challenges confronting longer-term sustainability of social purpose entities by aligning incubation and acceleration with national priorities, while equipping them with strong outcomes orientations. These propositions can then be connected to the pipeline of different forms of outcomes contracting being developed by the Social Contracting pillar. Supplementing this, different sources of capital are pooled through the Social Investment Fund pillar to enable easy draw-down and plug gaps in the conventional investment market that often underserves social purpose entities.

Creating cross-pillar synergy is a hugely complex undertaking, requiring long-term planning and work plan choreography. This is easier said than done. For example, unexpected or external shocks, such as COVID-19, necessitated urgent track changes. Additionally, population needs are complex and constantly shifting, and it takes time to establish and sustain partnership across different spheres.

Conclusion

Abu Dhabi offers an intriguing example of a jurisdiction that is consciously attempting to reconfigure the local system in order to activate a wider set of actors and align them around clearly defined social development objectives. In doing so, the Government is not simply ‘pushing’ for change but can instead be seen to socialise, familiarise and incentivise different system players to create the ‘pull’ for change. A few features are especially noteworthy:

- There is a published national framework setting out key social priorities. This facilitates partners to coalesce around clear points of focus.

- There is a dedicated agency given the mandate of leading on outcomes-focused approaches. This provides the local ecosystem with a clear ‘north star’ that has specific responsibilities and accountabilities for outcomes.

- There is a multi-strand approach underpinning ecosystem building to trigger and sustain outcomes, looking at both demand and supply side issues, and exploring synergies across strands in order to amplify collective impact.

The ultimate goal of this transformation is a future where economic prosperity and social development go hand-in-hand, so that value creation is sustainable and human-centred. This is a journey that the Emirate has embarked on recently, and it will be instructive to revisit the theories of change underpinning its ecosystem transformation approach over the coming years.

Dr Chih Hoong Sin is a consultant to the Government of Abu Dhabi.