Growing an international innovation in a local ecosystem requires a strategic approach

Posted:

6 Jul 2020, 1:16 p.m.

Author:

-

Chih Hoong Sin

Expert Advisor, Social Outcomes and Social Investment

Chih Hoong Sin

Expert Advisor, Social Outcomes and Social Investment

Topics:

Impact bondsRegions:

AsiaSocial Impact Bonds (SIBs) are a UK innovation, emerging in 2010, that shifts funding of public services away from activities and outputs towards outcomes by transferring some or all of the financial risk of non-delivery of outcomes from Government to social investors. While SIBs have captured the imagination of politicians and policy makers globally, we should resist uncritical replications of existing or historic models.

It is naïve to think that countries sharing common characteristics necessarily share the same motivations for engaging with SIBs, or end up with the same models. For example, while SIBs have been associated with neoliberal welfarism (Betzelt and Bothfeld, 2011; Dowling, 2017), I have written elsewhere about how SIB development in Japan and UK displayed significantly different features despite both being high income countries with significant national debt (Sin and Tsukamoto, 2018).

Stakeholders in Abu Dhabi are therefore keen to develop a clearer idea of how their local ecosystem may support or hinder the design and implementation of SIBs. Rather than ask the question of: “Which SIB model should we implement here?”, stakeholders have instead been asking themselves: “How will our local context influence the way we go about developing SIBs?”. In addition, stakeholders are also interested in: “How should we go about embedding social outcomes thinking and practice in a way that is authentic to the Abu Dhabi context?”.

The Ambitions for Developing the Abu Dhabi ecosystem

The ambition for SIBs in Abu Dhabi is to enable a thriving SIB ecosystem driven by six key goals:

In Abu Dhabi, it would be a mistake to look at SIBs only through the lens of discrete projects. Stakeholders in Abu Dhabi have prioritized system mapping and are taking a strategic approach that sees SIBs as part of a wider effort to enable system change. It is instructive that Her Excellency Salama Al Ameemi, Director General of Ma’an: the Authority of Social Contribution, asserted that: “It is part of our wider mission to think differently when it comes to developing our ecosystem in Abu Dhabi, and SIBs will enable us to deliver solutions to social challenges in partnership with Government, the private sector and civil society.”

At the most basic level, a SIB requires (a) outcome payer(s), (b) social investor(s), and (c) service provider(s). There are of course multiple additional stakeholders that may come into play depending on need and context. In the case of Abu Dhabi where SIBs were an alien concept as recently as in early 2019, and where thinking and practice around improving social outcomes through public policy is still largely unfamiliar, stakeholders have identified a fourth core group – (d) intermediaries that can provide expert technical, financial and relational support effectively within the local ecosystem.

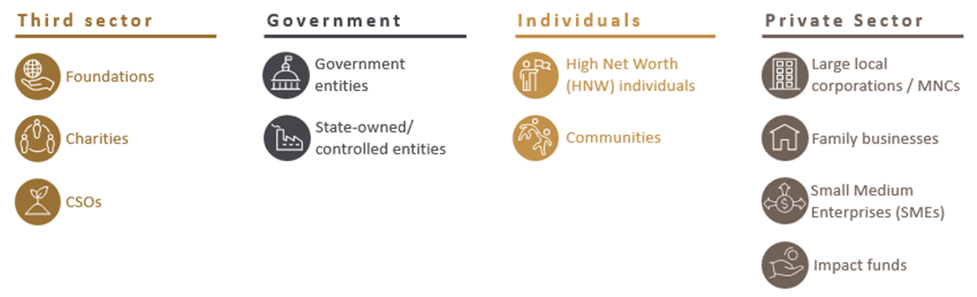

The Abu Dhabi context contains identifiable players that may potentially play a role in the SIB ecosystem. This may be illustrated, crudely, below.

Repurposing the Foundation Blocks

However, the existence of specific types of entities is no indication of ability and willingness to work in support of SIBs. Abu Dhabi has a number of notable characteristics that exert an influence on the direction of SIB development. For example, the United Arab Emirates ranks highly in the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) World Giving Index and is in the top 10 ‘biggest risers’ since the publication of the first Index in 2010 (CAF, 2019). The cultural context in Abu Dhabi also means that family businesses and intergenerational wealth management is established and recognised.

At the same time, current resources are not orientated towards supporting SIB development. For example, family businesses in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are the region’s largest contributors to social and charitable causes (Mamore MENA Intelligence, 2014), and have certainly been identified as key potential SIB players in Abu Dhabi. To unlock the massive potential of family businesses to contribute purposively to the enhancement of social impact at scale requires a change in mindset and a change in practice, since family businesses are overwhelmingly wedded to the usual practice of giving out grants and making donations (Adra et al., 2017).

More broadly, while impact investment is starting to take off in the UAE just as it is globally, there are important differences in the forms and emphases arising from different types of local opportunities. For those involved in SIB development, it can be challenging to re-orientate conversations away from existing orthodoxies and established models. Two in particular come to mind.

First, the well-established model of philanthropic giving means that it can be tricky explaining to key players why we are not asking for ‘donation’, which is what they are used to. Second, the well-developed market for financial instruments and commercial investments further means that stakeholders often mistake SIBs to be a new financial instrument. This has meant that initial meetings often involved legal teams and colleagues steeped in the regulatory regime around financial instruments.

Distinct narratives had to be formulated over time to speak directly to different stakeholder groups in a way that makes sense to the local context. For example, in Arabic, the translation of the term “Social Impact Contracting” is far less ambiguous and better understood in the Abu Dhabi context than the term “Social Impact Bond”.

It was important to build on current strengths in the local ecosystem, drawing links to known models but simultaneously extending the narrative. For example, anchoring conversations to concepts and practice such as zakat and family businesses, the narrative around SIBs is founded on the same underlining principle of ‘doing good’. This is well understood in the Abu Dhabi context, with clear local supporting infrastructure. At the same time, the messaging of SIBs in Abu Dhabi goes further, by encouraging these stakeholders not just to ‘do good’, but to ‘do good well’.

In addition, the models of banking in Abu Dhabi usefully builds on Islamic finance, which is growing in size and scope. SIBs offer interesting avenues for extending models of Islamic financing (Hayat, 2013; UNDP, 2014).

This involves shifting the focus away from financing as an end in itself, towards thinking of financing as a vehicle to achieve social impact purposively rather than incidentally. This means having to be strategic and systematic, and thinking of finance not only through an ‘input’ lens, but also in an outcomes-focussed manner. More importantly, it behoves stakeholders to measure and evidence social outcomes rather than to assume that positive outcomes are generated simply due to good intentions.

Innovating Through Gap-filling

I have argued elsewhere that the emergence of SIBs in the UK can be understood as one of the logical consequences of currents coursing through British public policy and public service development for many decades. For example, the UK’s long history of public policy innovation, its engagement with evidence-based policy and practice, and its familiarity with cross-sector collaboration in public service design and delivery can be seen as ‘building blocks’ supporting the emergence of SIBs (Sin, 2020).

Since 2010, SIBs have travelled far and wide. In the process, they have evolved. In Abu Dhabi, as in a number of other countries more recently where the evidence on outcomes is scant, SIBs are actually seen as vehicles for driving the development of the evidence base. This is a remarkable reversal of the ‘norms’ established in the UK and the USA.

In the Abu Dhabi context, there are gaps in what we conventionally think of as the ‘building blocks’ supporting SIBs. Yet, instead of treating these gaps as insurmountable barriers, stakeholders in Abu Dhabi have been behaving in a way that exemplifies the saying: “Necessity is the mother of invention”. The idea and execution of SIBs in Abu Dhabi perform a much wider function to reconfigure the local ecosystem in ways that support wider long-term efforts at embedding social outcomes at the heart of public services and public policy. For example, they give focus to measurement, repurpose parts of philanthropy, and redefine state – society relations.

As a matter of priority, SIBs are seen as a means through which Abu Dhabi can stimulate the growth of a vibrant and diverse social sector. Her Excellency Salama Al Ameemi said that: “Abu Dhabi has been one of the first to look to leverage this important pillar for the delivery of social programmes. Our mandate to create a flourishing Third Sector in Abu Dhabi will be realised through diverse channels of support, including SIBs, as an innovative and internationally recognised tool that raises private investment to support our high-impact agenda, in addition to leveraging knowledge, expertise, networks and funding.”

The SIB experiment in Abu Dhabi is therefore far more ambitious than an exercise in designing discrete projects.

Note 1:

Ma’an: the Authority of Social Contribution was established in February 2019 by the Department of Community Development in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi with the aim of bringing together the government, the private sector and civil society to support a culture of social contribution and participation. Ma’an will deliver solutions for social challenges with five pillars of work: a Social Investment Fund, a Social Incubator programme, a Social Volunteering programme, the introduction of new forms of Social Impact Contracting such as Social Impact Bonds, as well as Outreach Management. More information about Ma’an can be accessed by visiting their website at: https://maan.gov.ae/

Note 2:

Traverse is a London-based research and consultancy company that helps organisations involved in public services to deal with complex and controversial issues through effective engagement, robust evidence, and strategic change management. Dr Chih Hoong Sin, Traverse Director, is Expert Knowledge Partner supporting Ma’an and other stakeholders in Abu Dhabi to explore and implement innovations that improve social outcomes. More information about Traverse can be accessed by visiting their website at: https://traverse.ltd/.