Keeping it real about how results-based funding leads to better impact: A contextual roadmap for discussing the impact of RBF models

Posted:

4 Jun 2024, 9:32 a.m.

Author:

-

Jonathan Ng

Fellow of Practice

Jonathan Ng

Fellow of Practice

Topics:

Outcomes-based approachesTypes:

Fellows of Practice

Jonathan Ng is a Visiting Fellow of Practice with the GO Lab, a foreign service lawyer with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University Law Center. The views expressed herein are only those of the author. In this blog, he argues that a proper understanding of the role that results-based funding plays requires a proper understanding of the wider context in which the funding model sits.

Jonathan Ng is a Visiting Fellow of Practice with the GO Lab, a foreign service lawyer with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University Law Center. The views expressed herein are only those of the author. In this blog, he argues that a proper understanding of the role that results-based funding plays requires a proper understanding of the wider context in which the funding model sits.

When discussing the impact of results-based funding (or “RBF,” including outcomes-based contracting or “OBC”), it is important not to conflate the impact of the underlying intervention with the impact of the RBF model used to fund it. With increased attention on using innovative finance to fund traditional development programmes, we rush to glamorise creating new funding models as a solution to shortcomings in “traditional development.” But this can lead to conflating causation with correlation between the use of a particular RBF model and the impact of a programme. This occurs, for instance, when we hype new and innovative funding models for development, or attempt to analyse the so-called “DIB effect” (development impact bond) on development. The risk is that we overstate the need to scale new RBF models for their own sake.

Take, for example, a programme that utilises a proven, evidence-based intervention like the graduation approach to poverty that is funded by a DIB. If the activity was successful, it would be a mistake to conclude that it was because of the DIB model, unless there is evidence that shows a causal link between the use of that particular DIB design and the efficacy of that activity. It is otherwise possible that the activity would have been effective regardless of how it was funded. The reality is that to isolate the impact of a particular RBF model, you would need a proper comparison group. This requires a counterfactual using the same programme where the only difference is using a conventional funding approach. But this does not typically exist in practice because of limited resources. Further, the same RBF model could be used, but succeed in one programme and fail in another due to its design.

Instead, perhaps we should do more to promote applying an RBF mindset when using existing funding instruments. In other words, we should focus more on scaling effective RBF design principles over new RBF products. This includes more analysis and discussion around best practices for how to better define, price, and verify milestones. Emphasising an RBF mindset over new RBF products is more sustainable because it does not require funders (especially government) to seek new authorities or educate their staff about entirely new funding models. When introducing new and innovative approaches, it is often easier and more effective to work within existing bureaucratic systems. With U.S. government grants, for instance, fixed amount awards are a type of existing grant instrument where payments are made for achieving milestones, not just reimbursing costs. When designed well, fixed amount awards can be an ideal RBF instrument without the need for any third parties or added transaction costs.

Additionally, we should centre our RBF discussions around beneficiaries, not funders. It is good to encourage more innovation in how we fund development, but let’s not lose sight of how a programme actually improves the lives of real people and communities. Highlighting the innovative thinking of funders and the launch of new innovative finance products means nothing to beneficiaries if no actual (and better) development impact was achieved.

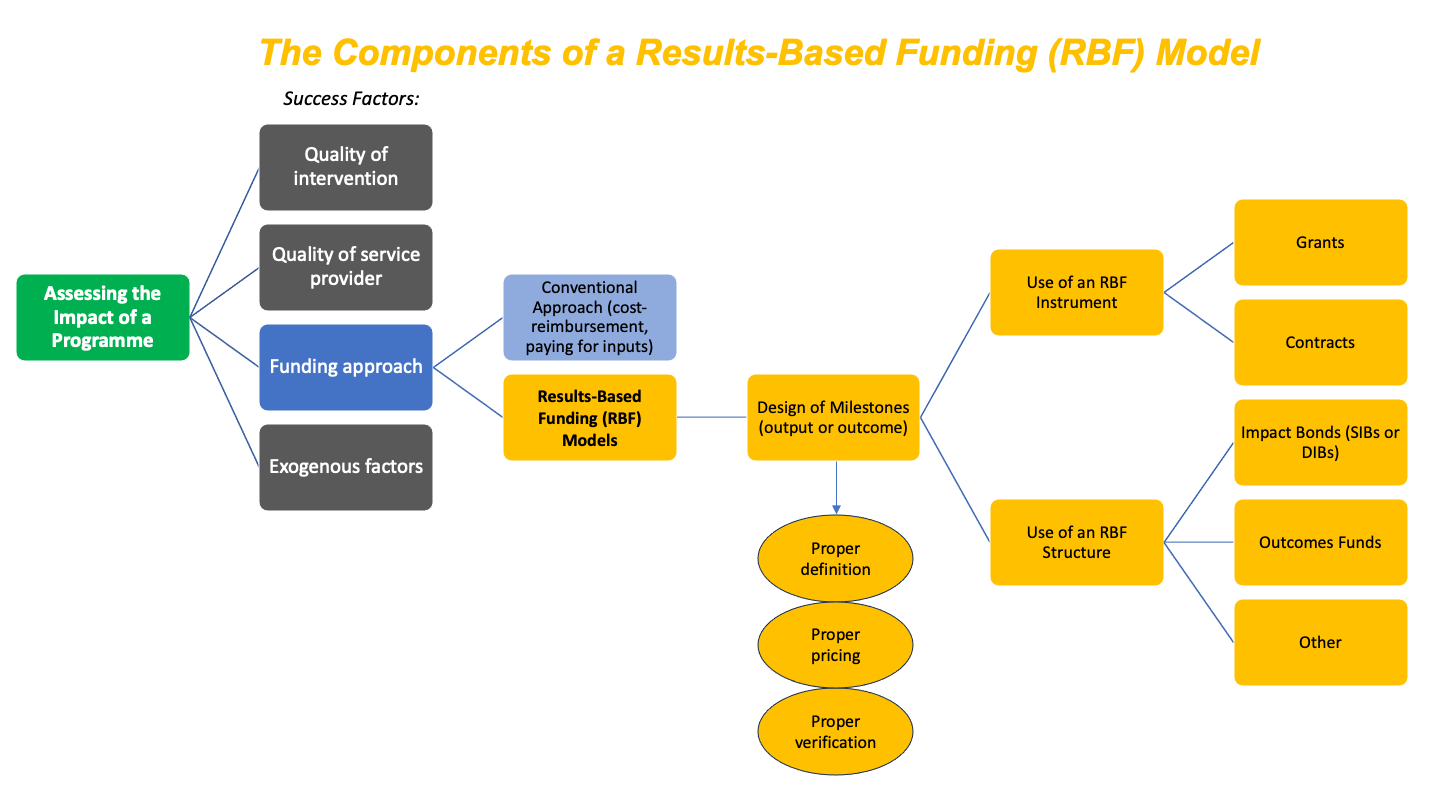

To guide any RBF discussion, below is a roadmap to help identify the key factors and specific components of any RBF approach that can influence the success or failure of a programme:

Using the roadmap, before discussing an RBF approach, it helps to first acknowledge and address:

- How the type of intervention selected matters. If you rely upon a bad intervention (meaning wrong approach, wrong timing, wrong context), it will not matter how innovatively it gets funded. Conversely, a good intervention that is funded in a conventional manner can be a big success.

- How the quality of the service provider matters. In the business world, some companies are better than others, and the quality of the people performing the work sets them apart. The same applies for the development sector and NGOs. If you choose the wrong service provider in the first place, it will not matter how innovative your funding model is. Getting the vetting and application process right is essential.

- How any exogenous factors, like the COVID-19 pandemic, played a role (if applicable).

Then, when discussing the RBF approach that was used, it is helpful to first distinguish between the use of RBF instruments versus RBF structures. An RBF instrument is a standalone agreement, such as an individual contract or grant between just the funder and service provider, in which payments are made for achieving results. In contrast, an RBF structure often includes several agreements, which can be a mix of contracts and/or grants among many different parties, including funders, service providers, intermediaries and third-party evaluators. It is possible to have a mix of conventional (i.e., input-based, cost-reimbursement) contracts or grants and RBF instruments within a single RBF structure. But simply using an RBF approach does not equal success. As with any tool, RBF is only as effective as how it is used. The thoughtfulness and quality of an RBF design will determine whether that RBF approach was effective or not. No matter whether an RBF instrument and/or RBF structure was used, the same three core design elements apply to every RBF approach:

- Proper definition includes milestones with a scope that is ambitious, yet realistic and within the direct control of the service provider.

- Proper pricing includes a reasonable justification to support the amount to be paid for achieving a milestone that can mitigate resentment by either party for potential under or overpayment, and withstand external audit scrutiny.

- Proper verification includes simple, straightforward criteria for determining whether a milestone has been achieved that will minimise future disputes.

Ultimately, by better placing RBF approaches within their proper context, this can lead to more thoughtful conversations and analysis about the real value-add of using an RBF approach compared to conventional funding approaches.