- Impact bond

- Health and wellbeing

- Africa

Kenya

11 mins

In Their Hands

Last updated: 4 Sep 2022

This case study reflects on the experience of the ‘In their hands’ project, the world’s first Development Impact Bond with a focus on adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Project Location

Aligned SDGs

INDIGO Key facts and figures

-

INDIGO project

-

Commissioner

-

Intermediary

-

Investor

-

Provider

-

Official evaluator

- Hera

-

Target population

- Adolescent girls (15-19 years old)

-

Launch date

September 2020

-

Start of service provision

September 2020

-

Capital raised (minimum)

GBP 5m

(USD 6.20m)

-

Service users

362k+

-

Duration

18 months

-

Target number of service users

193,000 girls

(For Triggerise, the implementers, targets were set as sexual and reproductive health (SRH) visits. They expected to achieve at least 244,445 visits during the life of the DIB.)

-

Maximum potential outcome payment

USD 6,600,000

The problem

In Kenya, 13,000 girls drop out of school every year due to unplanned pregnancies [1]. The ITH programme’s main goal is to connect adolescent girls to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. It is expected that the uptake of SRH services will reduce the incidence of unintended pregnancies in Kenyan teen girls.

[1] Ochako, R., Temmerman, M., Mbondo, M. & Askew, I. (2017). Determinants of modern contraceptive use among sexually active men in Kenya. Reproductive Health. 14. 10.1186/s12978-017-0316-3.

The solution

The In their hands (ITH) programme’s main goal is to connect adolescent girls to SRH services.

A key part of the development of this programme is the Tiko platform. The Tiko platform was developed by Triggerise and it has a double purpose. It offers a list of clinics and health centres to girls and gives them the possibility to choose from this list. The platform uses a series of nudge tools to motivate girls to uptake SRH services, such as reminders, follow-ups, subsidies and instant rewards. Every time a girl uses an SRH service, she can provide feedback and rate the service. As a reward for this, the platform gives girls an amount of Tiko points that girls can spend in local shops in exchange for other products. At the same time, the Tiko platform enables the implementer, the investor and the outcome funder to keep track of outcome achievements (uptake of SRH services and contraceptives) in real time. This means that they can all actively be involved in discussions around programme implementation and collaborate towards finding solutions to potential problems in the implementation.

Before releasing the platform to the public, Triggerise worked to build a series of virtual ‘ecosystems’ in 19 Kenyan counties. They enrolled a group of pharmacies, retailers, on-the-ground mobilisers and clinics on the Tiko mobile application. Once the ecosystems are part of the platform, girls are ready to sign up and start using the services.

There are three ways in which girls can sign up to the Tiko platform: girls either sign up to the Tiko application on a mobile phone (they can enrol themselves or be referred by another peer)[1], or through one of the community mobilisers on the ground[2]. Girls can choose between three pathways to enrol: sending a WhatsApp or Telegram message, sending an SMS or using a Tiko membership card (no tech involved). Once they signed into the platform or enrolled with a physical card (with a mobiliser), girls can access a network of clinics and providers that offer sexual and reproductive health services including counselling about contraceptive options, and advice on sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Once a girl has used the service, using the Tiko platform, she is asked to rate her experience with the provider. The fact that girls are rating these services generates an incentive for health providers to improve their services. Moreover, it enables the different service providers and franchisors to keep track of the performance of the different ecosystems and understand which health centres provide better services than others. The cost of these SRH services is paid by the programme, thus creating a motivation for service providers to be part of the platform and retain a high rating from the participants.

[1] Girls who don’t have a phone can access ITH services through a membership card.

[2] A community mobiliser is an agent of change from within the community. Tiko mobilisers actively reach out to the underserved members of their communities and connect them to various healthcare services through the application.

The impact

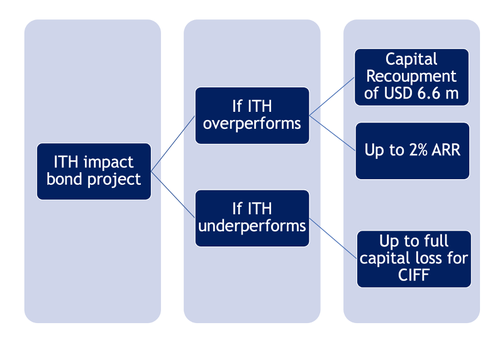

The ITH impact bond was designed and run as a pilot project to understand the viability of offering sexual and reproductive health services to adolescent girls under an impact bond framework. It was also a way to explore if non-traditional funders could be brought in to invest in adolescent SRH care. The impact bond was set to last for two years.

The investor recovered the initial capital and received a 2% ARR. Data from Triggerise shows that the project has outperformed all of its targets. For instance, 362,092 girls have visited a clinic or health centre due to a Tiko platform connection and 118,058 of them repeated their visit. The programme was expected to have 244,445 girls visiting a clinic and 45,000 of them repeating their visit (Triggerise, 2022).

According to the initial design of the DIB, the payments would be disbursed 80% depending on service delivery (girls accessing SRH services through Tiko) and 20% depending on an impact evaluation that was carried out by Hera. This impact evaluation was expected to measure the achievement of the medium-term outcome metric: contraceptive prevalence rate (or contraceptive uptake). Because of unforeseen delays in the procurement process, the impact evaluation started later than expected and data collection for the baseline started after 10 months after the intervention. The stakeholders decided that this evaluation was not able to show the real impact of the DIB and decided to pay 100% of outcome payments according to service delivery.

Rationale for using an impact bond model

Key stakeholders mentioned different reasons for using an impact bond model.

From the perspective of Triggerise, the implementer, the fact that payments were tied to two concrete outcome metrics generated a shift in the mindsets of all employees. The whole organisation was focused on achieving these outcomes and they aligned all their activities towards them. They describe the process of working under an impact bond as iterative, given that the outcomes focus demanded constant improvement and adaptation from the organisation.

Furthermore, the outcomes focus made them rethink how to run the ITH programme. For instance, Triggerise provided access to a dashboard to closely monitor outcome achievements and as both the investor and funder had access to this dashboard, they were kept up to date with the performance of the bond.

The CIFF team also recognised that the impact bond made them spend more time on analysing performance metrics and focusing on the desired results. Having launched the same programme with a grant approach, CIFF practitioners identified a clear increase in accountability levels. Before the impact bond project, they were only accountable to themselves as they had given a grant to the provider. After transitioning from grant-provider to investor, they still find the usual internal accountabilities and in addition, they become accountable to the outcome funder too.

According to the KOIS team, an impact bond was a timely model for these partners as they were looking for an opportunity to externalise risk to an investor, attract a diversified range of stakeholders, increase visibility of the project, and integrate some innovative elements (such as the use of real-time data). As they knew that the intervention worked well, experimenting with an impact bond model was an opportunity to scale up their project.

Enablers

Strong working relationship

One key enabler in the development of this impact bond was a strong working relationship between the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation and Triggerise. They had worked together running the same programme under a grant (from 2017 to 2020), which enabled them to generate a trustful relationship with shared values and common goals. According to KOIS, the previous relationship between CIFF and Triggerise had a positive impact in the structuring phase, as it is easier to work with partners who already have a relation (rather than working on the creation of that relation).

Experience in working with impact bonds

The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation had previous experience working with impact bond models. They were the sole outcome payers for the Educate Girls Development Impact Bond (India), which was completed in 2018 and had positive outcome achievements.

Successful experience with the same programme under a different type of contract

The outcome funder expressed that part of their interest in funding this project came from their awareness of the good results that the ITH team was achieving even before running an impact bond. The outcome funders did not have in mind a project where they would fund a completely new intervention, but a project where the theory of change was at least partially proven and the main investment was related to the technological component.

Availability of real-time data on outcome achievements

The Tiko platform not only enabled girls to have access to a personalised list of clinics and pharmacies, but it also generated a flow of real-time data that providers and funders could access through a dashboard to keep track of the achievements.[1] Although some girls use the SRH services with their membership card, not the phone application, all clinics and health centres use the application to verify data about the girls who are accessing services. This is why the real time data is representative of all the adolescents accessing services, not just the ones who are using the mobile application.

All stakeholders recognised that the data generated by the utilisation of the platform was useful in different ways. They could use the data to show proof to the payer that outcomes were achieved, to learn where the programme was underperforming and adapt, to mitigate risk of low performance, to test different solutions in cases of underachievement, and to prepare various nudging strategies for different Kenyan counties.

Challenges and risks

Added management costs

Comparing with their experience of running this programme under a grant, the CIFF team recognises that the impact bond model has an added cost. There is an increase in costs not directly related with the provision of the service. These costs are linked to performance management, risk management, and the need to coordinate the programme with a bigger group of stakeholders. Every stakeholder comes to the table with their own metrics of success and scrutiny requirements. The programme has to be able to comply with all of them. This adds a cost in terms of time and management of stakeholders’ expectations.

As the financial and development models become more complex, it is necessary to bring to the team an expert who can explain complex ideas to the rest of the team. These experts include an economist who can grasp the complexities of the financial model and an evaluator who can ensure that measurements are accurate and unbiased.

Exclusive focus on outcome metrics

Most stakeholders indicated that the strong focus on pre-set outcome metrics could be seen as a strength and limitation at the same time. An exclusive focus on metrics and targets may cause that service providers to be tempted to game the targets. In addition, an exclusive focus on particular metrics could incentivise service providers to work hard toward those targets but not work towards bigger outcomes achievements. For instance, a provider could be incentivised to get girls to attend a clinic but would not receive any incentive (or payment) to get the same girl to develop other types of healthy behaviours.

Measurement errors and baselines

Measurement errors pose a significant risk to impact bond projects. If outcomes are achieved, but the evaluation is not able to capture those results, the service provider and investor will not receive a payment. One particular problem with the baseline of this project is connected to some delays in the procurement process. The evaluator was contracted later than expected and the baseline was done in July 2021 (10 months after the start date of service delivery). This presented a serious challenge in terms of measurement. If many girls who already accessed the platform were part of the study, the baseline could be biased. Biased baselines could affect projects by overpaying or underpaying for outcomes.

Difficulty to set outcomes that are both valuable and achievable

The KOIS team highlighted the difficulties to design outcome metrics that were both relevant and measurable. The paradox lies in the fact that an evaluator needs a long period of time to measure highly valuable outcomes (such as a significant decrease in the rate of adolescent births). Given that this pilot was an 18-month impact bond, it was difficult to design metrics that were tied to outcomes, rather than activities. Even if outcome funders usually prefer to set metrics related to impact, investors and implementers may find themselves preferring metrics related to outputs, as they are in a better position to manage and evaluate them. In sum, what organisations value and what can be tied to payment do not necessarily coincide.

Difficulties related to running a SRH programme without government engagement

One of the challenges that this project faced was the lack of engagement from the national government which is ultimately responsible for the public health system. The beginnings of this project were difficult because a few months before the start date of service provision, the health authorities were discussing the possibility of enacting new regulations that could restrict access to contraception. The ITH programme clearly advocates for broadening the access of adolescent girls to SRH services.

Little room for managing targets

The KOIS team highlighted the fact that Triggerise had achieved the targets 5 months before the expected time. In case of overachievement, there is no extra reward for the implementation team. The KOIS team highlighted the need to find new ways to incentivise the implementers to both go beyond the targets and do their best and move towards a model where initial targets can evolve, instead of staying fixed during the whole life of the project. This new way of thinking of targets would be beneficial for those cases where initial targets were not challenging for the providers or unrealistic.

Insights and lessons learnt

The three parties agreed that the ITH DIB had been a positive experience where key lessons should be documented and shared.

The implementer was able to prove the scope of their platform and how much the data behind it could help projects adapt and improve. They also identified the need to re-think the model so that there is more incentive to think of the bigger picture instead of solely focusing on pre-set outcome metrics. This would encourage projects to achieve not only pre-agreed impact but also other positive impacts that were not foreseen in contracts.

The investor raised the issue of value for money analysis and the fact that the sector needs to reflect more on potential ways of reducing the costs of setting new impact bond projects. Even if these projects achieve positive social outcomes, it is still unknown if there is another model to achieve the same outcomes in a more cost-efficient way.

The outcome funder was interested in the opportunities that the use of technology could bring for future projects. In addition, the FCDO signalled that the lessons from this project will be key to improve the design of the next phase of the ITH programme. The United Nations has consulted the stakeholders about additions and improvements to the original design of the service. The FCDO suggested that the programme could be improved by seeking a more active engagement from the government, including HIV services in the basic programme, including mental health services and adding a new branch that could also attract boys to the conversation. The KOIS team recommended adding a bonus for overperformance, so as to incentivise providers to make the most of their time under an impact bond.

As of July 2022, the United Nations Joint SDG fund has invested USD 7 million to scale up the ITH programme. This new tranche will be a three-year programme to improve access and uptake of sexual and reproductive health and HIV services among low-income adolescent girls in 10 counties in Kenya. In addition, this new phase of the DIB will also have more engagement from the public sector as the national government will be a member of the project committee.

Recommendations

Most of the challenges and risks highlighted in previous sections are common to other development impact bonds. For instance, several organisations have highlighted the fact that impact bonds often imply added management cost. This is why it is vital that the different parties are clear about the rationale for using this mechanism and what is the added value that an impact bond could add to the programme. The question that remains unanswered is whether the added costs are worth the added benefits. In the case of the ITH DIB, it would be interesting to commission a study to compare the results of the programme delivered under a grant and the results of the programme under a DIB model to better understand not only how costs differ but also how benefits are achieved in each case.

Discussions around outcome metrics are also common in the field. As impact bonds are focused on predetermined metrics, it is key that the parties agree on the appropriate indicators. In this sense, the GO Lab guide to setting and defining outcomes can be helpful. The general recommendation is to select targets that are reasonable to achieve in the period of time of the specific project and measurable at acceptable cost and effort. When there is no reasonable and measurable outcome target for the period of time of the project, a sound theory of change can justify the selection of a proxy indicator, based on activities rather than outcomes.

Several organisations have highlighted the fact that the focus on a set of metrics can be seen as a strength and weakness of the model at the same time, and have suggested the possibility of introducing more flexibility in the outcome’s verification stage. However, this would also open the possibility for organisations to overbid to win a contract and then use the flexibility to renegotiate targets down.

The fact that the baseline was done 10 months after the start of service delivery affected the payment structure of the DIB. This was related to unforeseen complexities with contracting an evaluator for the DIB. As the main stakeholders agreed that it was not fair to work with a late baseline, the DIB paid outcome payments exclusively on a service delivery basis. In addition to finding ways to reduce costs, it is also necessary to improve the organisation’s capacity to procure and contract key services for the project in a timely manner.

The aim of this case study was to highlight factors that favoured the impact bond model and those that presented challenges or difficulties. The next step of the ITH programme is to scale up one more time under a new impact bond model that will be based in Kenya and funded by United Nations. Many of the difficulties signalled by CIFF, Triggerise and FCDO will be addressed and other organisations will be included in the project, as it is expected to receive more upfront investment, deliver more services and for more service users.

Acknowledgements

Representatives from the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), Triggerise and KOIS were interviewed between February and March 2022. We are thankful to all of them for their time and generosity in sharing their insights and experiences.