Overview of Social Impact Bonds: A briefing note for senior management in local authorities

This briefing has been developed to provide senior managers in local government with a high-level overview of social impact bonds. It will also address some of the most frequently asked questions in relation to this approach to commissioning public services.

Overview

Terms like “outcome based commissioning”, "outcome based contracting" and "payment by results" are used inconsistently and interchangeably. Broadly, however, they are all referring to a form of contracting out services that allows central or local government to pay a provider only when specific outcomes are achieved. The focus on outcomes may help public authorities enhance service quality and the productivity of public spending, by clearly defining the expected outcomes, monitoring them and paying only when they are achieved.

A social impact bond (SIB) is one form of this type of outcomes-based contracting. What differentiates SIBs from other, similar ways of contracting, is the involvement of so-called social investors. These are investment organisations who have a joint social and financial motivation, and their involvement serves two purposes: firstly, to cover the upfront capital required for a provider to set up and deliver a service prior to receiving payments for outcomes achieved; and secondly, to carry some or all of the financial risk of outcomes not being achieved (and therefore payment not being made).

Although there is no single agreed definition of a social impact bond, most definitions understand a SIB as a partnership aimed at improving the social outcomes for a specific group of citizens or ‘beneficiaries’. The service is set out to achieve measurable outcomes established by the commissioning authority, for example a Local Authority or a central government department, and the investor is repaid only if these outcomes are achieved.

The UK has been playing a pioneering role in this area, launching the world’s first SIB in 2010 in the criminal justice sector in Peterborough. There are more than 40 such projects across the UK as of September 2018, with many more in the pipeline. To date SIBs have been used to address a broad range of issues, including reoffending, homelessness, mental health, youth unemployment and children’s social care.

Why use social impact bonds?

Government is increasingly looking to test innovative approaches to managing demand, improving value for money and tapping into new sources of funding, such as social investment.

The social impact bond model has emerged in response to these challenges, and it builds on the government’s commitment to foster more cross-sector collaboration with the voluntary and the private sectors to tackle complex social problems. In this context, SIBs may be seen as a funding mechanism that allows VCSE organisations to deliver a payment by results contract without shouldering financial risks, whilst also unlocking private capital, as well as the expertise of social investors.

Unlike other public service commissioning models, the measurement of social outcomes is a necessary component for a SIB, since this functions as the trigger for payments by the commissioning authorities and is the basis on which investors are repaid. As such, SIBs may be seen as an innovative tool for delivering better social outcomes whilst ensuring value for money of public spending.

See Chapter 2 of the GO Lab's introduction to social impact bonds for more information about the debate around SIBs, including the key benefits and limitations.

Value for Money

Well-designed SIBs ensure value for money through a number of mechanisms:

- The

payment by results element ensures commissioners only pay for outcomes that are

achieved, rather than provision of pre-specified services

- Given

the requirement for evidence on outcomes achieved, SIBs contain a natural

evaluation element. Applied adeptly in the longer term, this allows

organisations to build evidence around ‘what works’ and ensures future

interventions can achieve greater value for money

- The

development of a SIB includes

elements of cost-benefit analysis, ensuring interventions are supported by a

robust business case

- The involvement of an investor can bring in an added dimension of performance management, above and beyond what commissioners have capacity to perform on their own.

SIBs as tools of public sector reform

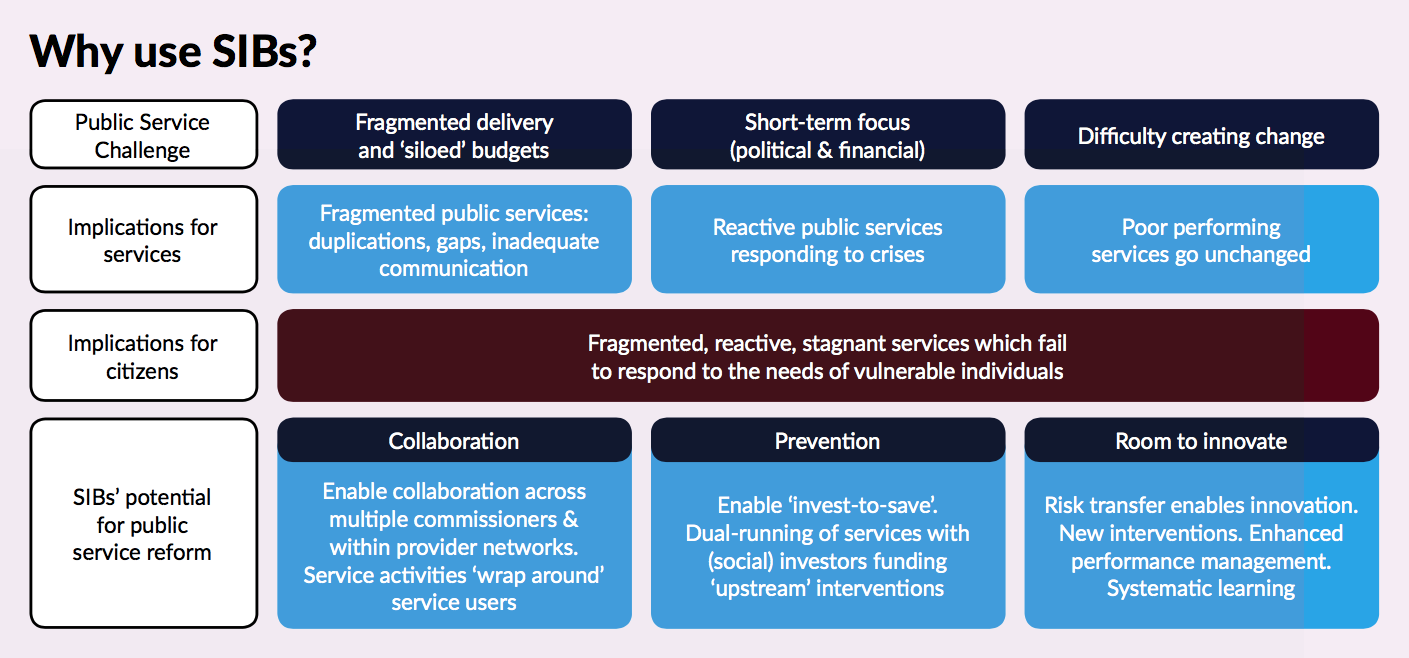

SIBs have the potential to improve outcomes by addressing three key public service challenges:

The GO Lab's research so far has suggested that SIBs might be useful tools in helping to tackle perennial public service challenges:- Fragmented delivery and 'siloed' budgets - duplications, gaps and difficulty working across service boundaries

- Short-term focus (political and financial) - reactive public services responding to crises

- Difficulty creating change - insufficient capacity to take risks and try new things

Collaboration

- SIBs have often facilitated collaboration across multiple commissioners and within provider networks. Pooled outcome budgets can enable collaboration across organisational boundaries.

- Greater flexibility for service providers enables services to ‘wrap around’ service users, responding flexibly to their needs by integrating a range of relevant support services.

Prevention

- Well-designed

SIBs could enable an invest-to-save approach by channelling investment into

interventions that prevent future problems, and can potentially generate savings

- Social

investment potentially facilitates the dual-running of services so that

‘upstream’ interventions can be introduced

Innovation

- Well-designed

SIBs can enable risk transfer from commissioners and providers, which may enable

the adoption of new interventions, enhance performance management capabilities,

and build the evidence base upon which to make future commissioning decisions.

What level of political support is there for social impact bonds?

SIBs started as a Labour project under Gordon Brown, grew under the coalition government and continue to have political support. SIBs seem to have generally enjoyed cross party support, as the potential benefits of SIBs appeal to politicians across the political spectrum. In August 2018, the Government produced the Civil Society Strategy which renewed their commitment to SIBs. A timeline mapping the key government strategies and activities in relation to supporting the development of social impact bonds is available here.

What is the evidence around the impact of SIBs as a tool for improving social outcomes?

The social impact bond landscape has evolved significantly over the past eight years, and evidence is starting to emerge around the use and impact of social impact bonds.

The GO Lab produced an evidence report in July 2018 entitled Building the tools for public services to secure better outcomes: Collaboration, Prevention, Innovation. This report looks at the state of play of all UK SIBs to date. It finds that the approach may lessen perennial public sector challenges, but we need to seize the opportunities to learn from where they work well and where they don't. You can read more about this report and the key findings on the GO Lab site.

More research needs to be done to understand the 'SIB effect' - whether SIBs work better than other more traditional commissioning methods, and if so, in what circumstances. This is a research objective of the GO Lab.

Social investment

What is social investment and who are the investors?

Social investment is the use of repayable finance to achieve a social, as well as financial, return. The UK is widely recognised as one of the most advanced social investment markets in the world. In 2016 the Government published its strategy on supporting the social investment sector in the UK, committing to use social investment as a way to transform public services.

Social investors can be individuals, institutional investors, dedicated social investment funds and philanthropic foundations, who invest through their endowment. More information about social investment in the UK can be found on the Good Finance website.

Why is the term “social impact bond” still being used, if SIBs are not technically bonds?

The term “social impact bond” has been used in the UK for the past eight years. Changing this terminology may cause confusion among stakeholders, but some suggest that it should be termed a 'partnership' or similar as this may be more representative of what they are. A glossary of other key words often used in this field is available on the GO Lab website.

Why should local authorities provide payment for outcomes through SIBs and not grants?

Unlike grants, as a funding mechanism, SIBs ensure that government only pays for desired outcomes achieved by a service. As mentioned above, SIBs may have the potential to improve collaboration across different sectors, foster innovation and channel investment into preventive services. There is a growing appetite for socially-motivated investors to use their capital as a driver of sustainable growth, directed towards investments that have a positive impact on society. SIBs enable government at both central and local level to access this growing impact investing market.

However, social impact bonds are not suitable for all social policy areas and services. A mixture of grants and social investment will likely continue to play a key role in government funding.

Why would local authorities use a SIB in place of a payment by results (PbR) contract?

Public authorities interested in commissioning SIBs should always start by undertaking an evidence-based options appraisal of all available funding models. Depending on the local context, the problem that is being addressed and the provider market, a commissioner may well decide that it is more appropriate to use other commissioning mechanisms such as a grant, a fee-for-service contract, or PbR.

Reasons for using a SIB over standard PbR contracts are as follows:

1. In a conventional PbR contract, service providers are only paid when they achieve the outcomes: it is the service provider that carries the financial risk if outcomes are not achieved. Consequently, it can be a challenge for service providers to find or cover the up-front capital to deliver a project at scale. With SIBs, the social investor bears the financial risk and provides up-front funding to service providers to set up the project.

2. Depending on the type of investor and their way of working, the involvement of investors can bring additional capacity and expertise in project management and data analysis that local VCSE organisations might lack. Some of the VCSE organisations that have worked with social investors have reported that they valued this input from social investors and that it contributed to building their expertise in house.

3. The combined expertise of commissioners, providers and investors creates partnerships that actively work together to find solutions to social problems.

Instead of using a social investor, could the Government (or the service provider) not borrow money at a cheaper rate?

For many authorities, a lack of funding or resource capacity is a significant inhibitor of developing new approaches to services. Authorities might not be able or willing to invest in the first instance due to limited access to finance or the difficulty of accepting the project’s risks.

Only paying when outcomes have been achieved means that the working capital required to set up and run the services sits outside the public purse in the first instance and it is paid back only in case of success. This makes SIBs a more attractive funding mechanism than obtaining loans from mainstream banks and other conventional lenders. Moreover, some social investors work closely with investees, providing management support and specialist expertise, as well as financial resources.

The costs of developing and implementing a SIB should be carefully considered against the value that the proposed service will create. Commissioners should consider the overall costs and benefits, seeking guidance from resources offered by the GO Lab in order to do so.

How much return on investment does a commissioning authority have to pay?

Social investors seek blended social and financial returns, and the potential to make a profit on the initial investment is intended to compensate investors for the performance risks they take on under a SIB model - after all, there is a chance they will lose money. SIB commissioners can put a cap on the maximum amount of outcome payments they are willing to make, which also caps the investors maximum return. Rates of return vary widely, and the government is committed to encouraging more transparency in the system around the rates of return - something the GO Lab is pushing for.

Developing a social impact bond

As a new form of commissioning, developing social impact bonds can place additional demands on commissioners and can be technically challenging at first. At the same time, the potential benefits of this approach have prompted a growing number of local authorities to explore and engage with the model, providing examples of how to adopt new practices and share learning.

The Government seeks to catalyse the development of scalable and replicable SIBs, and has previously made available to local authorities outcome funds such as the Life Chances Fund (though this is now closed to new applicants).

The GO Lab offers advice and support to local authorities interested in exploring social impact bond models of service provision. This includes:

- Advice surgeries - every Tuesday morning we provide advice and support online or via phone. These can focus on any element of designing and implementing SIBs

- SIB readiness framework - This online resource explores the considerations that need to be made at each stage of developing a SIB, including best practice and when there’s more work to do. They break down the complex and perhaps unfamiliar processes in bitesize chunks.

- Technical Guidance - Our technical guidance provides more in-depth support on topics in the SIB readiness framework. This will give you a deeper understanding of the different stages and is written in a clear and accessible way.

- Events and webinars - There are many events scheduled throughout the year that support commissioners who are developing a SIB. They foster peer learning and allow offer opportunities to hear from sector experts.

- Past and current SIBs - We have a project database where you can find the details of all the projects that have been launched in the UK to date. We also have numerous case studies of SIBs in different sectors that provide an in depth look at key aspects of the SIB and how it works.

Further information

Government Outcomes Lab

The Government Outcomes Lab (GO Lab) is a partnership between the Centre for Social Impact Bonds and the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. Launched in July 2016, the GO Lab conducts academic research that seeks to deepen the understanding of outcome based commissioning and provides advice to local commissioners who are developing outcome oriented models of public service provision, such as social impact bonds.

Centre for Social Impact Bonds

The Centre for SIBs aims to catalyse the development of SIBs at scale. As part of the Office for Civil Society at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, the Centre for SIBs provides expert guidance on developing SIBs, shares information on outcome based commissioning and supports the growth of the social investment sector.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/social-impact-bonds

Life Chances Fund

The Life Chances Fund is an £80 million fund set up by Government to contribute to outcome payments for locally commissioned SIB projects that aim to tackle complex social problems.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/life-chances-fund

Good Finance

Good Finance provides information on social investment for charities and social enterprises.