Outcomes-based contracting

This guide offers an introduction to outcomes-based contracting, including its place among other methods of contracting out public services, the theoretical pros and cons, and the evidence to date.

Overview

14 minute read

Cross-sector partnering for service delivery

Traditional forms of public service contracting tend to link payments to the inputs or activities of the service. However, public services exist to achieve tangible outcomes with service users - that is, changes which positively impact upon their life experience.

There are a range of ways in which an outcomes orientation can be incorporated into public services, in order to focus on the overall improvements in the life of service users, rather than participation in individual services. Outcomes-based contracting is one way of achieving this, by linking payments directly to the achievement of outcomes with service users.

Outcomes-based contracting, through which payments are linked to the achievement of outcomes, sits in a broader range of public service sourcing strategies.

In-house service delivery or grant funding to external provider organisations focuses payment on inputs, including financial resources and staffing.

Fee-for-service contracts pay providers to deliver a specified activity to users.

Results-based financing (RBF) approaches tie payment to the achievement of pre-specified objectives. In some forms of RBF, payment is tied to outputs, such as completion of an activity.

Outcomes-based contracting is a form of RBF. Payments are linked to the achievement of specified outcomes. Impact bonds are a subset of outcomes-based contracts, in which private investors provide the upfront capital to cover service delivery costs.

Those in favour of outcomes-based contracts propose a range of policy objectives that may be achieved through their use. These claims can be grouped into three broad themes:

- Incentivising desired behaviour - parties to outcomes-based contracts are incentivised to behave in a more positive manner. Contracting organisations will allow providers to be more flexible, providers will adopt a more innovative and evidence-based approach, and investors will finance public services.

- Managing risks - as payment for a service is only made upon the achievement of outcomes, the risk of not delivering outcomes is transferred away from public sector contracting organisations to providers and/or investors.

- Reducing costs/increasing effectiveness - the costs of public services are reduced through increased competition, freedom in service design, and private sector terms and conditions. Effectiveness is simultaneously improved by a focus on evidence-based interventions.

However, there are a number of counterarguments which cast doubt on each of these purported benefits. Attempting to understand which side of each of these debates may be correct leads us to examine the evidence from outcomes-based contracting in practice.

Unfortunately, the empirical evidence on outcomes-based contracting is limited, and sometimes conflicting. Outcomes-based contracting and other forms of RBF have been explored in a range of contexts around the world, with mixed results. There is a lack of evidence on the contracting mechanism, with most evaluations focusing on the intervention delivered through an outcomes-based contract (OBC), rather than the merits of the OBC itself.

Despite limitations to the evidence surrounding outcomes-based contracting, some high-level lessons may still be drawn from evaluations of the approach.

It is important to understand the overall fit of outcomes-based contracting for a particular social challenge. There should be a clear purpose for the use of an OBC, and a full understanding of the costs associated with them.

During the design of the OBC, care should be taken to segment the target population and define outcomes to align closely with policy objectives, to avoid perverse incentives. Collaborative design with key stakeholders can help in this process.

As the new form of contracting is implemented, transitional arrangements and support and training may ease the move from more traditional contracting.

Finally, evaluation of the OBC should be considered from the outset. Data must be collected to understand the impact of the approach and how it may be improved, and where possible should be shared transparently to facilitate learning from the project.

Cross-sector partnering for service delivery

Traditional models of contracting out public services have generally focused on the activities service users will participate in. This payment model is called fee-for-service (FFS). A particular service is specified, and providers are paid to deliver that service.

However, public services ultimately exist to deliver outcomes for service users – that is, positive changes in the life of the individual. Outcomes-based approaches to public services have long been advocated in academic literature, and in recent years they have increasingly been applied in practice.

Bovaird and Davis (2011) identify five main ways in which outcomes are currently incorporated into public services, based on evidence from the United Kingdom:

- Outcomes-Based Accountability - When assessing public bodies, outcomes can be used to define responsibilities and what counts as success.

- Outcomes-Based Commissioning - When assessing need and designing public services, outcomes can be used to agree priorities with stakeholders and design relevant interventions.

- Outcomes-Based Procurement - When selecting which providers should be contracted to deliver services, outcomes can be used in the decision-making process.

- Outcomes-Based Contracting - When implementing services, outcomes can be used to frame the relationship between contracting organisations and service providers, through an outcomes-based contract.

- Outcomes-Based Delivery - When delivering a service, outcomes may influence the way in which providers shape their activities.

These different categories all reflect a broader outcomes orientation in the contracting out of public services. Instead of focusing on individual services, an outcomes orientation focuses on what ought to change for service users and structures service provision accordingly. For example, in the domain of employment, instead of focusing on particular skills training or job search services, an outcomes approach would focus on the long-term employment of a job-seeker as the ultimate desired goal of a service. This might mean a much broader range of services are considered to support users into employment.

Outcomes-based contracting ties this outcomes orientation directly into the incentive structure of public service contracting. In an outcomes-based contract, payment is wholly or partly dependent on outcomes being achieved. Service providers are therefore directly incentivised to deliver outcomes with service users. The more outcomes they deliver, the more they will be paid. In the case of employment, this might mean paying providers for each service user who achieves employment for a pre-specified, sustained period.

Outcomes as an incentive system

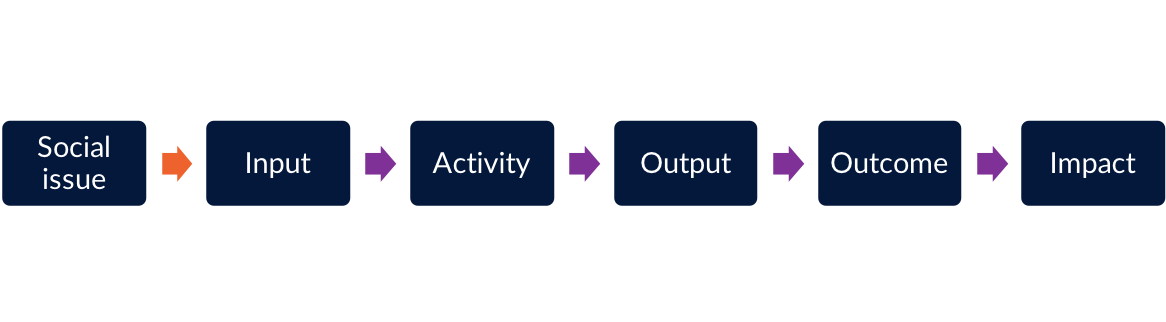

Outcomes-based contracting, where the pursuit of outcomes forms the basis of the contractual incentive system, sits on a spectrum of mechanisms through which public services may be sourced. Different sourcing strategies reflect payment being linked to different points in time in the process of improving social outcomes. This process is often shown in a simplistic ‘logic model’ like the one below:

More “traditional” sources of public service provision are concentrated towards the left of the logic model. These include in-house provision by the public sector, as well as grant funding of external organisations and fee-for-service contracting.

When services are provided in-house, or are delivered by external organisations through grant funding, payments and accountability are focused on the input of resources to the logic model. These inputs, including financial resources and staff, support service delivery.

In a fee-for-service (also known as fee-for-activity) model, a particular service is specified by the contracting organisation, and providers are paid to deliver that service. Payment is focused on the activity that service users participate in.

Results-based financing (RBF), also referred to as Payment by Results (PbR), is a method of contracting out public services, whereby payment to providers is based – wholly or in part – on the achievement of pre-specified objectives, including outputs and outcomes. PbR is generally less prescriptive than fee-for-service, with providers given flexibility in the way they deliver the service to achieve results.

In some forms of RBF, some portion of payment is based on the delivery of outputs. These are the goods and services supplied by an intervention that are intended to lead to outcomes for service users. Providers are paid for the number of outputs that are achieved, such as the number of people who complete a skills training programme.

In contrast, in an outcomes-based contract, payment is wholly or partly based on the achievement of outcomes. An outcome is the thing that actually changes for the individual as a result of the service. For example, if completion of a skills training programme is the output, the outcome for the service user might be gaining and sustaining employment. Accordingly, the provider in an outcomes-based contract would be paid if a service user achieved sustained employment for a pre-specified period of time.

Impact bonds (IBs), or Pay for Success (PFS), are a type of outcomes-based contract, which are differentiated by the involvement of a third-party investor, who provides the upfront capital required for a provider to set up and deliver a service. For more, see our introduction to impact bonds.

The debate: is outcomes-based contracting a better option?

The previous section placed outcomes-based contracting, where outcomes provide the basis of some proportion of payment, within the wider scope of public service contracting. This explains what outcomes-based contracting is, but it doesn’t explain why a contracting organisation would pick an OBC over those alternatives. Albertson et al. (2018) outline the theoretical debate surrounding outcomes-based contracting in their chapter Outcome-based commissioning: theoretical underpinnings, which is the basis for this section.

According to its proponents, outcomes-based contracting may offer a range of benefits over alternatives. The chapter highlights three broad policy objectives that outcomes-based contracting might address. First, that OBCs incentivise various parties to the contract to behave in more positive ways. Second, that OBCs allow parties to manage the balance of risk in service delivery, allocating risk to whichever party is best placed to manage it – for example, providers have more control over the risk of poor delivery. Finally, that OBCs can increase the efficiency and/or reduce the costs of public service delivery. However, the authors also highlight a range of concerns surrounding outcomes-based contracting that threaten to undermine one or more of these policy objectives.

This section presents some of the arguments that supporters of outcomes-based contracting make in its favour, centred around these three policy objectives. It also highlights a range of concerns, which call some of the positive claims made about OBCs into question.

Incentivising desired behaviour

One objective of tying the financial incentives of a contract to the achievement of specified social outcomes is that it will lead the parties involved – contracting organisations, providers and, in the case of impact bonds, investors - to change their behaviours for the better.

Contracting organisations will be incentivised to focus on setting and measuring outcomes, rather than closely micromanaging providers to ensure the activities specified in the contract are being delivered. Providers will be incentivised to identify ‘what works’ to deliver outcomes. They will innovate and experiment with different approaches, and build an evidence base to inform future service design. In addition, the flexibility and transparent payment mechanism afforded by OBCs will encourage collaboration between providers to achieve outcomes. Finally, in impact bonds, investors will be incentivised to finance public services by the potential for both social impact and financial returns when outcomes are achieved.

Outcomes-based contracts aim to align the interests of parties around a common focus on outcomes. This in turn has a range of benefits for the service, including flexibility, innovation, and access to new sources of financing. However, other features of outcomes-based contracting may have the opposite effect, leading parties to behave in undesirable ways.

Misaligned incentives (sometimes unhelpfully called ‘perverse’ incentives) can encourage providers to focus on achieving the outcomes specified in the incentive system of the contract, rather than responding to the wider needs of service users. OBCs risk ‘cherry picking’, where eligible individuals are not referred or accepted onto a service if they seem unlikely to achieve payable outcomes, ‘creaming’, in which providers focus their efforts on those individuals who are easiest to help, and ‘parking’, which is neglect of those who may be more difficult to achieve outcomes with. These behaviours are often referred to as ‘gaming’.

A related challenge involves measurement and attribution. For outcomes-based contracting to be successful, public sector contracting organisations should be able to confirm that outcomes have been achieved, and can be directly linked to the services delivered by the provider. However, it can be difficult to set simple, measurable outcomes that align effectively with complex social problems. Reliably attributing any outcomes to the service itself is best achieved through comparison to a reference group who did not participate, demanding additional resources.

Managing risk

Outcomes-based contracting can also be used to transfer some of the risk associated with public service provision from government to other parties who may be better placed to manage those risks. As payment is only made when outcomes are achieved, the financial risk of a service failing to deliver those outcomes is transferred to providers, or in the case of impact bonds, investors. Rather than government paying upfront for a service that may not be effective, it can defer payment until positive outcomes have been achieved. If positive outcomes are not achieved, then government will not bear the cost.

In addition to the direct transfer of financial risk, OBCs may help government to mitigate its risk in a number of other ways. These include attracting new providers to the market to limit the risk of individual provider failure, and ‘depoliticising’ service delivery by making providers responsible for decision-making around service design and delivery.

However, the private sector are likely to be significantly more risk averse than government. As a result, they will require higher potential financial returns, which may wipe out cost savings. In addition, if risk is not appropriately distributed, the provider may find themselves subject to restrictions or ‘micromanagement’ from investors and/or contracting organisations. The contractual terms that govern the allocation of risk between parties can be complex, requiring considerable resource to set up and oversee. And certain types of risk, such as reputational and political risks, are not easily transferred.

Reducing costs/increasing effectiveness of public service delivery

The third major policy objective of outcomes-based contracting is to reduce the costs and increase efficiency of public services, purportedly through a range of different mechanisms.

As providers are given freedom over the design and delivery of services, they can focus on evidence-based interventions, improving the effectiveness of services. They may also be expected to reduce overheads and other costs. Private sector organisations may be able to offer less generous terms and conditions than the public sector. Incentivising new entrants to the market will increase competition, driving down costs. Finally, as payments are deferred until outcomes are achieved, the future costs may be discounted.

However, the financial and effectiveness benefits of outcomes-based contracting are not entirely straightforward. First, while outcomes-based contracting is supposed to improve effectiveness by encouraging providers to adopt evidence-based interventions, this is at odds with the intention to incentivise innovation discussed earlier. In addition, suggested improvements to the effectiveness of services are predicated on providers identifying evidence-based interventions and having the freedom to implement them. However, evidence of ‘what works’ is not always easy to interpret and integrate into services, especially when translating it from one context to another.

The cost-saving promises of outcomes-based contracts face their own questions. Outcomes-based contracts involve multiple actors, and the eligible cohort, desired outcomes, and prices paid for the achievement of outcomes must be well specified. These features are likely to result in increased transaction costs associated with developing and managing the contract. It is unclear whether the mechanisms proposed above can outweigh these costs. For example, proponents claim that outcomes-based contracts may attract new providers to the market, increasing competition. However, public service quasi-markets often suffer from a lack of competition, and – especially given the increased risk transferred to providers – it is not entirely obvious why OBCs would solve this issue, and produce competition-derived efficiency gains.

The evidence

There are some significant policy challenges which, according to its proponents, outcomes-based contracting may be able to solve. OBCs promise to align stakeholder behaviour around a focus on social outcomes; provide a more balanced distribution of risk between government and providers/investors; and reduce costs or increase the effectiveness of public services. However, there are also clearly valid concerns surrounding the approach, which threaten to undermine one or more of these policy objectives. Theory alone cannot give us conclusive answers as to which side of the debate is right. To move forward, we need to understand how outcomes-based contracts work in practice. Do outcomes-based contracts deliver on their promise, or do their costs outweigh their benefits?

Unfortunately, there is no straightforward answer to this question. There have been a limited number of rigorous studies of outcomes-based contracting to date. Of those that have been conducted, conclusions have been mixed. In addition, it has proved difficult to separate the effect of the type of contract that was used from that of the actual work that was done on the ground. The GO Lab is currently conducting a systematic review to improve the usefulness of the evidence base.

A snapshot of evaluations from a range of contexts around the world is presented below. These studies highlight some of the disagreements about the pros and cons of outcomes-based contracting and other forms of RBF, as well as some lessons that may inform future contracting.

World Bank Program for Results

The World Bank’s Program for Results Evaluation was published in 2016. It assessed early experiences with the design and implementation of Program for Results operations. It identified that government participation and ownership was positive, that there were similar project preparation costs but higher implementation costs, and that payments were made in a timely manner. Its initial recommendations focused on strengthening the results framework, and monitoring and reporting systems, to ensure that indicators linked to payments are closely aligned with the theory of change and project objectives.

UK Government PbR Schemes

In 2015, the UK’s National Audit Office reviewed the country’s largest payment by results (PbR) schemes. This included projects on a range of domestic social policy areas, a welfare to work programme from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), a family support programme from the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), and two pilot offender rehabilitation programmes in HMP Peterborough and HMP Doncaster, overseen by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). In addition, it examined 19 PbR aid projects being delivered around the world under the Department for International Development (DFID), responding to a range of development issues including water and sanitation, education and health.

The report notes that, to date, evaluations have largely focused on implementation rather than effectiveness or value for money. There is also limited evidence for the use of PbR as opposed to alternative delivery mechanisms.

Health sector RBF in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)

The Working Group on Performance Based Incentives, commissioned by the Centre for Global Development in 2006, evaluated a number of health contracts around the world involving performance-based financial incentives. It found significant improvements in key health indicators, including when rewards or punishments were relatively small.

However, the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for Health Services conducted an analysis of 10 systematic reviews and 4 direct evaluations of RBF projects in the health sector in LMICs. It found “limited evidence of the effectiveness of RBF and almost no evidence of the cost-effectiveness of RBF”.

Social impact bonds (SIBs) in developed countries

In July 2018, the GO Lab published a report on the evidence around impact bonds – Building the tools for public services to secure better outcomes: collaboration, prevention, innovation. We found that SIBs had the potential to overcome perennial challenges in the public sector through improving collaboration, encouraging prevention and fostering innovation. However, we also recognised the lack of evaluation and data available, as well as the fact that many SIB evaluations looked at the intervention rather than the SIB as a delivery mechanism.

Lessons learned

The previous section provides a brief overview of some of the evidence to date surrounding outcomes-based contracting, which paints an incomplete, and sometimes contradictory, picture of the approach. Some of this uncertainty may be addressed by further research, but this is of little help to those who have to make decisions now. In the absence of conclusive evidence, those looking to implement outcomes-based contracts should proceed with caution. However, some high-level reflections might prove useful.

While there is not a comprehensive answer as to when or how to develop an outcomes-based contract, there are nevertheless lessons that have been learned from previous attempts at the approach. In 2015, the UK’s National Audit Office (NAO) released two reviews of Payment by Results (NAO 2015; ICF 2015). From these reports, a number of 'lessons learned’ from experiences of PbR to date have been identified, and may prove useful to those hoping to develop an outcomes-based contract of their own.

Overall fit

There should be a clear purpose for the use of an outcomes-based contract to deliver a particular service. Contracting organisations should have a clear rationale for their use of an OBC over alternative methods of public service contracting. In addition, they must have a full understanding of the costs associated with OBCs. Resources are required to design, procure, manage and evaluate outcomes-based contracts, and these costs should be factored into any decision to pursue the approach.

Design

When designing an outcomes-based contract, it is important to carefully define outcomes to ensure they align with policy objectives, and minimise the risk of perverse incentives and gaming. While there is no consensus on the approach that should be taken to outcome definition, some features have been identified as important. Segmenting the target population can help to avoid gaming practices, by clearly defining the eligible cohort. Collaboration in design, with both providers and service users, can lead to better designed contracts and services.

Implementation

As the contract is implemented, it will be important to recognise the challenges associated with adapting to a new form of contracting, for all parties. Transitional arrangements can help to ensure service provision is maintained at a high standard, particularly in new or challenging markets. Contracting organisations should also be prepared to offer training and support to both commissioners and providers to give them the skills required to operate under an OBC.

Evaluation

Data is important for evaluating the success of an outcomes-based contract, to understand whether the approach improved the service and/or value for money. Evaluation will happen both during delivery, in order to inform performance management, as well as at the conclusion of the contract, to understand what worked well (and what did not). As the contract is developed, it will be important to consider the extent to which data and evaluation results can be shared, to provide transparency and facilitate learning from the project.

Acknowledgements

This guide was produced by Michael Gibson (Writer-Researcher), with the help of a number of members of the GO Lab team.

An earlier version of this guide was put together by Sue de Witt (Bertha Centre, South Africa), and reviewed by Jane Newman (Social Finance).