Procurement Guide

A guide to procurement for social impact bonds

Whilst procurement is often seen as a barrier to public agencies doing innovative things, there is greater flexibility in the regulations than many people think. When it comes to outcome based commissioning and social impact bonds, you might need to take advantage of this wriggle-room. This guide will explain the options you have at your disposal.

Who is this guidance for?

- Commissioners or policy advisors who are looking at the legal/ procurement implications of a new approach, particularly one that involves outcome based commissioning or social impact bonds

- Procurement or legal professionals looking for detailed guidance on procurement options for public bodies

- Local and national government, NHS bodies (CCGs/ STPs), Police and Crime Commissioners, and other public bodies who may commission public services

Navigating this guidance

Chapter 1 will give you a general overview of the 2015 changes to procurement rules and additional scope given by them, as well as your options for procurement in a SIB project. Chapter 2 follows exactly the same structure as Chapter 1, but gives you lots of extra detail if you want to know more.

'I need the basics' - Read 1.1 and 1.2

'I need to understand my options in full' - Read all of Chapter 1 (1.1 – 1.7)

'I need to understand the legal / regulatory backdrop to decisions' - Read 2.1 and 2.2

'I have a question about a specific scenario' - Read 1.3 and 1.4

Thanks

We want to thank the following people for their contribution to developing this guide:- Jo Blundell, Director, Future Public

- Julian Blake, Partner, Bates Wells Braithwaite

- Mila Lukic, Investment Director, Bridges Fund Management

- Adam Kybird, Associate, Bridges Fund Management

- Paul Riley, Executive Director, Outcomes UK

- Dr Domingos Soares Farinho, Professor of Law, Lisbon University

Disclaimer

The content of this guidance is to the best of our knowledge. It does not constitute legal advice from the University or from Government, and you will still have to make your own decisions and take legal or other professional advice if necessary.

Chapter 1: Overview

31 minute read

1.1 The challenges of procurement in outcomes contracts and SIBs

Outcomes contracts and SIBs are often co-developed with investors, providers or both. This can present some new challenges from a procurement perspective. You might recognise some of the challenges below. The good news is they all have a solution!

| The practice of consulting and collaborating prior to competition | Often, providers and investors bring useful know-how which helps to develop a good service. But that means they have an advantage in any open tender process down the line, which can make you vulnerable to challenge from other providers if they lose. |

| Provider intellectual property | Linked to the above, providers might put a lot of time and effort into developing a good service with you, only to lose out in an open tender process. This feels unfair to them and can put providers off collaborating with you. |

| Leadership of the development by a provider | Sometimes, it is the providers who lead on the development of a new service or proposed outcomes contract - but it is still the commissioners who have the say on whether to procure it, and how. |

| A lack of real competition to deliver innovative services | Because they are often new and unique, many outcomes contracts / SIBs have a limited pool of suppliers who would be able to deliver them. So an open tender process won't get many bids. How do you know you have got value for money? |

| Considering Social Value | How do you take into consideration aspects like whether a provider is local and / or whether they are a VCSE (which can be very important in outcomes contracts) - without prejudicing the process or flouting the rules? |

| Engaging social investors | Social investors often have much to bring to the process, but they are not providers. Do they need to be procured? At what stage should they be involved? Do they need to be kept at arms' length throughout? |

1.2 The Rule Book

In public procurement we have a duty of value and we tend to think this means we always need to make providers compete to ensure we get the best deal. However, the Public Contract Regulations 2015 recognise that the quality of competition and fair access to an opportunity are not the sole means by which public value is secured through procurement.

Where a provider market exists, it remains the case that the public interest in securing value is best served through a well-managed and open tender competition. However, where there isn’t an established market, the new regulations allow for negotiated and restricted processes, and these should be adopted where a good quality open competition is not possible. The Social Value Act and Public Contract Regulations 2015 state that public organisations should look for the Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT), which includes social and environmental value alongside price and quality.

Social, health and education services are subject to the so-called ‘Light-Touch Regime' which enables commissioners to run any procurement process they choose provided it adheres to the EU treaty principles below:

Principle of proportionality: the cost of the procurement exercise (for bidders) should be proportionate to the value of the services.

Engagement of the willing: there is no need to create artificially broad (and expensive) tender competitions if you are confident that only a few organisations will respond (because only a few can deliver what you want).

The principle of transparency: the competition process should give equal and fair treatment (you still have to advertise the opportunity and produce the tender documents even for a highly restricted process).

Note that while

you can choose the type of procedure used to confirm with the above three

principles, you do need to be able to defend your choice.

Market

engagement is encouraged prior to the competition, acknowledging the need for

collaboration. Pre-tender engagement is not subject to the legislation, but the

same principles should probably apply to mitigate the risk of challenge in any

later procurement process.

Authorities may still use the familiar procedures of open competition or competitive dialogue / competitive negotiation. Certainly for social impact bonds, including scope for dialogue during the procedure is strongly encouraged to enable a deal to be finalised. But the full Competitive Dialogue procedure is resource-intensive for bidders and may exclude some providers from participating, breaching the principle of proportionality described above. Consequently, the new regulations present some lesser-known procedures that can be useful: Innovation Partnership, VEAT, and PIN Notices. These are all described later in this guide.

More detail on the recent changes in the rules is available in 2.2 The Rule Book (additional detail).

1.3 Social Value

Social value is particularly relevant to outcome based commissioning and SIBs because it is a process that often engages voluntary sector organisations with a wider social purpose.

The Social Value Act 2015 does not require any specific sets of considerations, but it may be advantageous to consider what additional benefits to the community, over and above the services in scope, might be delivered by the provider as a result of the contract.

Evidence from research conducted by OECD suggests that there is less ‘gaming’ from SIBs delivered by non-profit organisations, compared to PbR which engages for-profit organisations. This does point to the need for trust in the means by which services are delivered, and this can mean a preference for a non-profit / VCSE provider. If you feel that even the Social Value Act does not give you strong enough means to express this preference, the rules do allow you to reserve contracts for certain types of organisations (i.e. non-profits) under Section 77 of the Public Contract Regulations.

More detail on social value in 2.3 Social Value (additional detail).

1.4 The lesser-known procedures

Innovation partnerships

These should be used “where there is a need for the development of an innovative product or service or innovative work and the subsequent purchase of the resulting supplies, services or works cannot be met by solutions already available on the market” (Public Procurement Directive 2014/24/EU, recital 49).

Innovation partnerships are useful where neither the provider market nor the commissioner has developed a service method or model that is capable of being contracted. It is essentially a contract for mutual experimentation.

- Though it has not

been used in the UK to date in any type of procurement, it could be very useful

in overcoming the procurement considerations of SIBs in particular, by covering

both development and delivery.

- The key result of an

Innovation Partnership is a service specification / delivery model, and the

duration of the contract(s) is determined by how long it will take to deliver

this – whether or not the intended contract is to be paid on outcomes (as in a

SIB) or on service.

- The ownership of

intellectual property should be explicitly dealt with in the contract, so that

you don’t end up in a situation where there is information you need for a

competitive process but it can’t be disclosed by either party.

- Although the

procedure is silent on who pays for the design/development, commissioners and

providers may look to co-invest for mutual benefit.

See more in Chapter 2 on Innovation Partnership.

Prior Information Notice (PIN)

These give a restricted opportunity for providers to submit a proposal where there is limited competition.

- The PIN is the most

frequently used of the accelerated restricted procedures.

- It advertises the

opportunity through the OJEU process and provides tender documents for

respondents, and therefore it provides the opportunity for open access to

opportunity.

- However, the minimum

period allowed for a response is short (10-15 days depending on the service),

so there is limited opportunity for a provider without prior involvement.

- The procedure is

used in SIBs where a provider has led the development of the service (and may

be the direct recipient of a development grant). Commissioners should still

consider the wider market interest and opportunity for competition before using

the procedure.

See more in Chapter 2 on Prior Information Notices (PIN).

Voluntary Ex Ante Transparency Notice (VEAT)

This provides retrospective notice through the OJEU process of a decision to award a contract to a provider without competition.

- A VEAT is the

reverse of a PIN in that it does not provide for a competition. It should only

be used where there is a reason to believe that a single, named organisation is

in a unique position to deliver a service to the requirements of the

commissioner.

- Prior experience

alone does not make a provider uniquely capable, as another organisation might

develop a service if presented with an opportunity through a conventional tender

process.

- It is up to you as a

commissioner to be able to defend the decision to use a VEAT. You should

consider how to conduct a test of the market appetite in a way that is proportionate

to the value of the opportunity (and show that you have done so).

- After awarding the

contract, there is a standstill period (10-15 days depending on the service)

that allows organisations to object and demand access to a competition.

- N.B: the VEAT should

not be used to “reward” providers who have invested in developing an idea,

unless the organisation is uniquely capable of delivering it.

See more in Chapter 2 on Voluntary Ex-Ante Notices (VEATs).

Co-operation agreements

These should be used where commissioners want to collaborate with other public sector bodies to deliver a contract, rather than to contract to a private or VCSE sector organisation. No competition is required. See more in Chapter 2 on Co-operation agreements.

1.5 Engaging investors

One thing that can confuse procurement in SIBs is the involvement of investors.

Investors can be involved in different ways at different times in the development of a SIB. At one extreme, investors have led projects from the start. At the other, investors have dealt only with providers, and commissioners have had no contact with them at all. The reality is usually somewhere between the two.

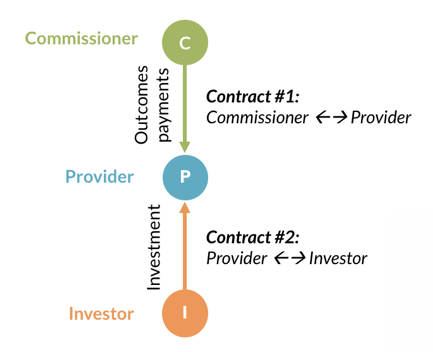

One way to think through this is to consider the eventual contracting relationship that is desired between the three parties: commissioner, investor and provider.

- Investors can partner

with a provider, who is the prime or principal contracting party. This is

simplest and works well when there is just one commissioner and provider.

However, if commissioners want to influence the type of investor that providers

engage with (e.g. to ensure they are mission-led), this needs to be tested with

the market and then built into the procurement process.

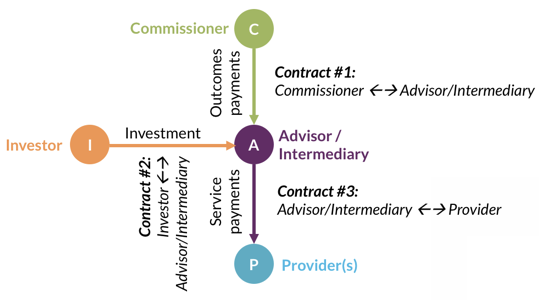

- Alternatively,

investors can be the prime or principal contractor, and sub-contract to one or

more providers. This may be preferable in more complex arrangements where there

are multiple commissioners and/or multiple providers. Investors would need to

participate in partnership with providers for this approach to work.

- Instead of the investor being the prime or principal

contractor, the advisor or intermediary can play this role. This becomes

important if there are multiple investors.

In some cases, investors have ‘co-invested’ alongside the public authority, and have then jointly procured a provider as partners. Whilst ‘co-investing’ is not subject to procurement, the choice of ‘co-investor’ should probably still use some form of competition to ensure good value in the investment terms.

You can read more about these options in Chapter 2.5 Engaging Investors (additional detail).

1.6 Three ways to procure SIBs and get value

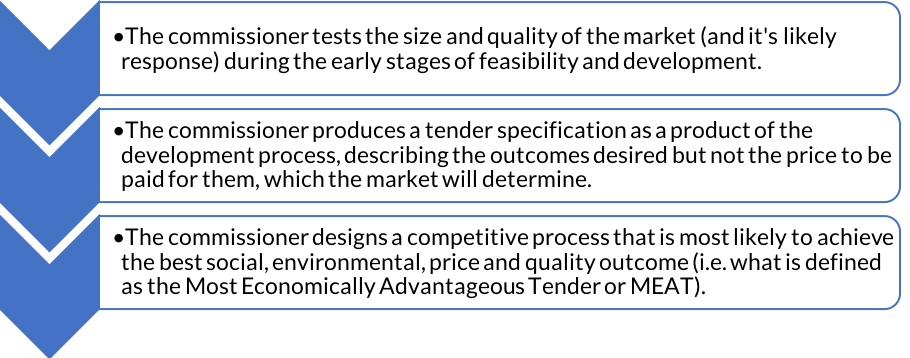

While these may not be the only ways to procure a SIB, they present three likely alternatives based on the particular circumstances of SIBs as described above.

- A restricted

competitive process i.e. PIN or VEAT

- An open competitive

process that will define the price to be paid

- An open competitive process against a pre-defined schedule of payment rates

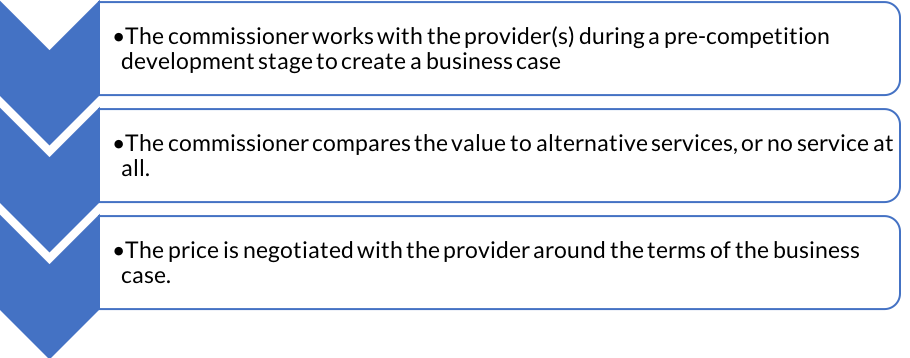

1. A restricted competitive process (PIN or VEAT) with a negotiated price

This approach is best if there are only one or two providers likely to be able to deliver the service. This could be because they have been involved in developing it.

Considerations:

Making sure that the deal doesn’t unravel if social investors get involved later in the process, and don’t like the look of the negotiated deal. This is one reason to get investors engaged early on during the negotiation.

Example: Travel Training

HCT developed a new service proposition around providing travel training to children using community transport services to enable them to travel more independently over time. No other community transport provider had a similar proposition. HCT secured development funding from CBO Fund and engaged multiple authorities in developing a SIB.

HCT had a unique proposition at the development stage – no other provider could demonstrate a track record. Furthermore, they had received the external development funds that enabled the service to be developed as a SIB, and that resourced the development of the business case with commissioners.

Commissioners needed to judge whether other organisations could develop a similar service in response to an opportunity to bid. HCT sought a restricted process and a VEAT process was used successfully with 2 authorities. There was a challenge on the process by another provider with a third authority, and they conducted an open competition as a result.

2. An open competitive process that will define the price to be paid

This approach is best if there are several providers likely to be able to deliver the service. If any of them have been involved in developing it, then care should be taken to ensure they do not have an unfair advantage in the competition.

Considerations:

Social investors should be included either as respondents or as part of provider bids

There may be some need for capacity building in social sector organisations to participate in a competition based on paying for outcomes.

Example: Reconnections

The Worcestershire Reconnections service is designed to address loneliness. It is the first and only SIB to date to tackle this area and resulted in producing a business case that demonstrates the cost benefit of intervention. The service was co-commissioned between Worcestershire County Council and several local CCG commissioners. The idea came out of work by Social Finance and Age UK who created the initial business case that secured development grant funding. There was extensive collaboration prior to the formal stages of the contract relationship.

However, the commissioners chose to run an open procurement exercise that took 10 months, to give themselves some power to negotiate terms. Unfortunately, the only respondent were the team that had developed the concept – Age UK and Social Finance, supported by Nesta and Big Society Capital. So there was no competitive pressure in practice.

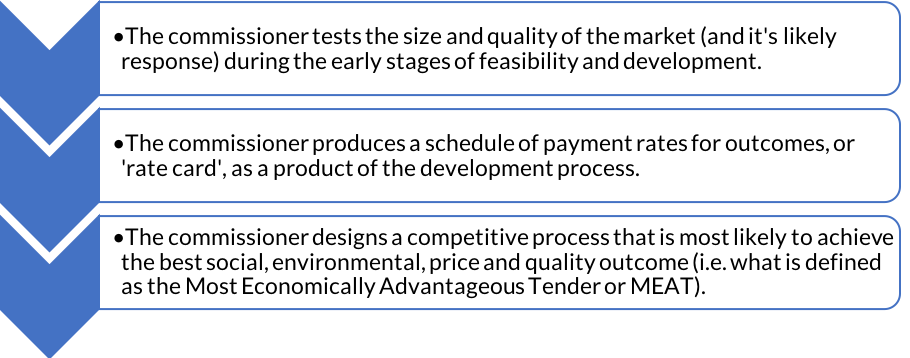

3. An open competitive process against a pre-defined schedule of payment rates or tariffs (a ‘rate card’)

This approach is most useful when commissioners are confident that they can define the value of payments for improved outcomes, because the costs of the alternative are easy to define e.g. the cost of keeping children in residential care.

It can also be useful where there are multiple lots across different commissioners, or different providers delivering to the same outcomes framework .

Competition becomes focused on quality of service and value of the impact, although bidders may also offer a ‘discount’ to the advertised price.

Considerations:

If the payment rates do not reflect the cost of delivery and provide the right incentives, they may encourage “gaming”.

Example: DWP Innovation Fund

The Innovation Fund was a pilot initiative aimed at supporting disadvantaged young people, and those at risk of disadvantage, aged 14 years and over. It paid for outcomes that were directly related to increasing future employment prospects.

The Innovation Fund was commissioned over two rounds via an open competition. DWP developed a range of proxy outcomes for gaining and sustaining future employment: re-engaging with education (by addressing truancy and behavioural issues); gaining educational qualifications; and entering apprenticeships and employment.

DWP specified a maximum amount they were willing to pay per outcome, which represented a proportion of the benefit savings associated with moving a disadvantaged young person into work. There was also a cap of £8200 per participant in round one and £11,700 in round two.

The list of payable outcomes, and amount per outcome, was published in the specifications for each round. Bidders then proposed the payments they expected for each outcome, often offering a discount on the published price. Bidders were allowed to ‘pick and mix’ from the list of outcomes and work toward outcomes appropriate for each young person up to the maximum cap.

A fourth option to consider

In some cases, investors have partnered with an authority to ‘co-invest’ in a service, and have then jointly procured a provider as partners. Under public contract regulations, the provision of finance does not have to be subject to competition, and this is the basis on which investors are sometimes engaged prior to any formal competition. However, they do have an effect on the cost of running a contract due to the cost of finance – but also add value in helping formulate the contract terms for the provider and, later, in performance management.

If an authority decides not to subject investors to a competitive process (for example, due to a desire to collaborate with a preferred investor), then it is sensible to sign a memorandum and to seek an understanding of the terms of finance on an ‘in principle’ basis. Whilst it may not be binding, it will provide some basis to negotiate.

Example: Mental Health Employment Partnership

Mental Health and Employment Partnership (MHEP) is a vehicle through which local commissioners of mental health supported employment services can procure a specialist intervention known as Individual Placement and Support (IPS). There are 3 contracts with Haringey, Tower Hamlets and Staffordshire. MHEP secured development grant funding from the CBO programme.

MHEP look to be appointed as investor partners under a Memorandum of Agreement, prior to a competition for a provider. The provision of finance is excluded from the Public Contracts Regulations. They then ‘co-commission’ with local authorities using a pre-defined specification, payment and outcomes structure and performance management process.

This means that there is no competitive pressure on the cost of providing finance (interest payments), but there is a shared interest in securing a service that delivers value and impact.

Haringey moved an existing IPS service already procured under the MHEP service. The other two authorities have run open procurement exercises for providers.

1.7 Good practice

A procurement plan

Define the procurement process in a plan that justifies the choice of approach. This makes the decision-making process about the procedure to be used explicit. The plan should cover:

- The rationale

for using an outcome based contract to commission (in other words, why use a

SIB or PbR rather than straightforward service contract)

- The basis on

which organisations will be engaged prior to the formal procurement, and in

particular the basis on which they share information, ideas and market

intelligence (soft market test)

- How other

stakeholders are involved, including other commissioners and service users

and/or their representative organisations.

- When and how

social investors are engaged

- Any capacity

building that might be required to enable providers to participate.

Transparency and intellectual property

One of the defining characteristics of outcomes-based commissioning is that it presumes a level of collaboration and shared value between the parties to the contract. However, commissioners should consider how that value is owned and shared to the public benefit. Knowledge and evidence should be regarded as an asset created through the contract, which the public body should retain access to. This means transparency should be required as a condition of the contract. There should be a commitment to transparency as part of the bid evaluation process, and open use of data and evidence as part of re-commissioning decisions. There is much more detail on this in Chapter 2 on Transparency and intellectual property.

Agility in delivery

One of the benefits of contracting on an outcomes basis is that it enables providers to flex the way a service is delivered as they learn more about it. This adapting to ongoing learning (typically backed up by data) is a key feature, and should be considered as part of the procurement process. Commissioners also need to be prepared for contract terms to change if necessary, since not all the flex required will be possible within the terms of a contract even if it is built in from the start.

Chapter 2: Additional details

2.1 The challenges of procurement in outcomes contracts and SIBs (additional detail)

In outcome based commissioning, it is more likely that commissioners and providers will work together collaboratively than in other forms of contracting, both to initiate the idea, and throughout the process of designing a specification or model for the service. It is this inter-dependency that can make the application of procurement processes that comply with the EU Treaty principles (shown below) more difficult to achieve. Moreover, on some occasions commissioners will start the procurement process with a clear idea of the desired outcomes, but not of the service or the preferred solution. It is in these less certain environments that applying procurement processes with confidence is more challenging. This guidance seeks to address these reservations.

Chapter 1.1 above summarises particular challenges that outcome based commissioning can present.

2.2 The Rule Book (additional detail)

The Public Contract Regulations 2015 (shown below) provide a new set of principles for public procurement that acknowledge the need for greater flexibility, and that put social value at the core of procurement decisions in the public interest. The new regulations formally recognise that “public authorities are major economic actors who have a big impact through their spending – and by consciously directing that spending differently they can drive positive social change and social innovation.” (Bates Wells Braithwaite, HCT Group and E3M (2016) ‘The Art of the Possible in Public Procurement’).

This means that organisations whose primary purpose is to create social value, whether social enterprises or voluntary sector, can be more fully valued in the process of procurement. The new regulations, following changes in European Union rules, provide for a more collaborative and ‘lighter touch’ set of processes, which is useful as commissioners consider how to put the regulations into practice when commissioning for outcomes. Importantly – the regulations allow for some limited circumstances where open competition is impractical.

Procurement processes as prescribed in European law have previously focused on quality of competition, and equal access to opportunity. Where services are well understood and a mature supply market exists, the prevailing view has been that commissioners will get the best value for money through a competitive process, and this principle remains paramount. However, in recognition that this arms-length approach may not serve the public interest in all circumstances, there have been some significant changes to European regulation to provide a greater level of flexibility.

One of the General EU Treaty Principles is proportionality, meaning that the cost and effort of the procurement process should be in line with the value of the opportunity. The Regulations mean that you need to make reasonable efforts to make an opportunity available to providers in the market, but not to an extent that it becomes an artificial competition because you already have a clear idea what you want. It can be used, for example, where the service intervention is highly specialised and the commissioner knows who the likely providers are (and there may be only one). The rules allow you to work with willing partners rather than present an opportunity for all, though it remains important to make it explicit that that is what you are doing, and why.

This principle is reflected in the new regulations through the Light Touch Regime, explained next. Within this newly granted flexibility, of course authorities may still choose to use the familiar procedures: open competition, or competitive dialogue / competitive negotiation. For complex procurements, contracting authorities typically turn to the Competitive Dialogue procedure, because straightforward open competition without dialogue may not enable bidders and commissioners to settle on a satisfactory set of terms. Authorities could also use an accelerated negotiated procedure (as well as restricted procedure under 2006 regulations), providing you can justify the rationale for the timescales.

Certainly for SIBs, including scope for dialogue during the procedure is strongly encouraged. However, the full Competitive Dialogue procedure is laborious for authorities and resource-intensive for potential providers (some of whom will not have the spare resources to risk on engaging in a bid, thus missing out completely even if they have the best solution). It does not necessarily adhere to the principle of proportionality described above. Consequently, the new regulations present some lesser-known procedures that can be useful: Innovation Partnerships, and ‘Single Action’ tenders through Voluntary Ex Ante Transparency Notice (VEATs) and Prior Information Notices (PINs). These are explained in section 2.3.

The Light Touch Regime

The so-called ‘Light Touch Regime’ applies to social, health and education services. Under the light touch regime, there is no specific requirement to advertise contracts in OJEU and there is no requirement for the commissioner to follow one of the specific procurement procedures (even where the value of the contract exceeds the €750k threshold explained below). Rather, the commissioner is free to use any type of procurement or design their own process, provided it adheres to the EU Treaty Principles, meaning it:

- is transparent

– people know the opportunity is out there and the basis on which the

decision will be made;

- treats all comers as equal – no-one is given preferential treatment during any part of

the process, i.e. no-one is allowed to ‘cheat’ – and doesn’t discriminate – you can’t exclude

someone because they exhibit certain characteristics (unless using Reserved

Contracts – see next section, ‘Social Value’);

- is proportional

to the size of the contract being let – meaning if a contract is relatively small

in amount, smaller providers must not be excluded by an overly laborious

process that they don’t have the resources to participate in. (But also meaning

that for larger contracts, the process is sufficiently robust that it is not a

cakewalk for certain suppliers).

In some ways similar flexibilities to the Light Touch regime were available under the ‘Part B’ services in the former regulations, which were not used much by risk-averse public authorities. But, the principle of designing a process to suit the circumstances, rather than following a procedure for its own sake, is now more explicit.

If the procurement is over 750,000 Euros (or the equivalent in pounds), then you need to consider the below requirements in addition to general adherence to the principles:

- A Prior Information Notice (PIN) or Contract Notice (CN) still needs to

be published, and a contract award notice when you award.

- The contract must be awarded in line with the procedure you described in

the PIN or CN (i.e. you cannot change tack mid-way through).

- The time limits provided for a response must be reasonable and

proportionate.

It is probably sensible to consider these things anyway, in helping to ensure your adhere to the Treaty Principles.

It is also important to note that there is now much greater scope for post-tender negotiations, particularly where projects involve innovative design or financial structuring. Authorities may ‘optimise’ as well as clarify final tenders.

The freedoms granted by the Light Touch Regime are important as enablers for good outcome based commissioning practice, but they are not widely adopted. The guidance set out in this document seeks to suggest how these changes can be incorporated in the context of procurement for outcome based commissioning.

The Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (quoted material for reference)

The Public Contracts Regulations 2015 implement the 2014 EU Public Sector Procurement Directives designed to provide a more flexible regime of procurement rules. The Regulations enable public sector commissioners to run procurements faster, with less red tape and with a greater focus on getting the right supplier and best tender in accordance with sound commercial practice. The implementation of the Regulations took effect from 26 February 2015.

Key changes introduced by the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 include:

SME participation - a greater focus on SME Participation, with contracting authorities being encouraged to have smaller procurement lots and restrictions on setting turnover requirements

Supplier selection - a simpler process for assessing bidders’ credentials, involving greater use of supplier self-declarations

Procedure changes and consultation - preliminary market consultations between contracting authorities and suppliers are encouraged, which should facilitate better specification

Innovation partnerships - this is a new addition that is intended to allow scope for more innovative ideas and for suppliers to enter into partnerships with the public sector authorities

Time limits – the minimum time limits by which suppliers have to respond to advertised procurements and submit tender documents have been reduced by about 30%

Light Touch Regime – there is no longer a separation of services into Part A and B and there is now a Light Touch Regime for Health and Social Services. The new Light Touch Regime provides significant flexibilities; there is a significantly higher threshold than for supplies and for other services (i.e. EUR 750,000 for public sector authorities) and authorities have the flexibility to use any process or procedure they choose to run the procurement as long as it respects the obligations set out in the 2014 Public Contracts Directive.

EU Treaty obligations (quoted material for reference)

Public procurement is subject to the EU Treaty Principles of:

• Non-discrimination

• Free movement of goods

• Freedom to provide services

• Freedom of establishment

In addition to these fundamental treaty principles, some general principles of law have emerged from the case law of the European Court of Justice, including:

• Equality of treatment

• Transparency

• Mutual recognition

• Proportionality

The EU rules around public procurement are contained in a series of directives that are updated from time to time. The most recent update of the EU procurement directives was in April 2014:

Public Sector: Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC

Concessions: Directive 2014/23/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the award of concession contracts

Utilities: Directive 2014/25/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors and repealing Directive 2004/17/EC

Public procurement is also subject to the World Trade Organisation Government Procurement Agreement.

2.3 Social Value (additional detail)

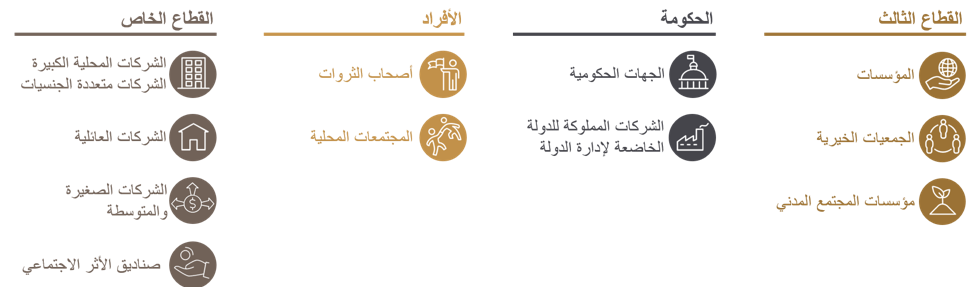

Outcome based commissioning often means engaging with charities, social enterprises, and other types of purpose-driven (as opposed to profit-driven) organisations – often known as ‘VCSEs’. When this type of engagement is important, the new regulations give commissioners more room to prioritise it through procurement processes. The Social Value Act 2012 also supports this (see explanation of the Act below).

The Public Contracts Regulations 2015 revise the definition of MEAT – Most Economically Advantageous Tender. Previously, assessment was made primarily on some balancing of quality and price. Now, there is a recognised need to weight the environmental and social aspects of the tender as well (even if the service is not an environmental or social one – though outcomes-based contracts will almost always be the latter). And according to the Social Value Act, the commissioner should specify how social value will be considered in the procurement process, and define the level of expectation in terms of social value produced.

Commissioners may go one step further in ensuring that a contract is let to a VCSE or non-profit organisation – by using a Reserved Contract (Regulation 77 of Public Contract Regulations 2015). This uses the procurement process to restrict the awarding of a contract to certain types of organisation, i.e. non-profits. It should be noted that Reserved Contracts have a maximum contract length of 3 years.

The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 (quoted material for reference)

Social value has been defined as “the additional benefit to the community from a commissioning/procurement process over and above the direct purchasing of goods, services and outcomes”.

Whilst there are many examples of providers delivering social value available to illustrate this, there is no authoritative list of what these benefits may be. The reason for this flexible approach is that social value is best approached by considering what is what beneficial in the context of local needs or the particular strategic objectives of a public body. In one area, for example, youth unemployment might be a serious concern, whilst in another, health inequalities might be a more pressing need.

In recognition of this, the Public Services (Social Value) Act does not take a prescriptive approach to social value. It simply says that a procuring authority must consider:

- How what is proposed to be procured might improve the economic,

social and environmental well-being of the relevant area.

- How, in conducting the process of procurement, it might act with a view

to securing that improvement.

In doing this, the Act aims to give commissioners and procurement officials the freedom to determine what kind of additional social or environmental value would best serve the needs of the local community as well as giving providers the opportunity to innovate.

The Act applies to public service contracts and those public services contracts with only an element of goods or works over the EU threshold. This currently stands at £113,057 for central government and £173,934 for other public bodies. This includes all public service markets, from health and housing to transport and waste. Commissioners will be required to factor social value in at the pre-procurement phase, allowing them to embed social value in the design of the service from the outset.

Source: Social Enterprise UK and Anthony Collins Solicitors in The Social Value Guide2.4 The lesser-known procedures (additional detail)

Innovation Partnership

The Innovation Partnership procedure was introduced under the 2014 EU Public Contract Directive and can be used “where there is a need for the development of an innovative product or service or innovative work and the subsequent purchase of the resulting supplies, services or works cannot be met by solutions already available on the market” (Public Procurement Directive 2014/24/EU, recital 49). The new procedure is designed to enable contracting authorities to select partners on a competitive basis, have them design an innovative solution tailored to the authority’s requirements, and then deliver it.

Under the Innovation Partnership procedure, a selection is first made of those who respond to the advertisement. Then, the contracting authority uses a negotiated approach to invite suppliers to submit ideas to develop innovative works, supplies or services aimed at meeting a need for which there is no suitable existing ‘product’ on the market. The contracting authority is allowed to award partnerships to more than one supplier.

With this process, what a commissioner is procuring is essentially the design/development process that leads to the final specification – and at the same time, the delivery of that specification – all through one partner. There are a number of key considerations in relation to moving forward with an Innovation Partnership:

- It is a procedure intended for mutual experimentation where the

standards of evidence to articulate of the problem do not exist, and therefore

a specification cannot be written .

- There is no hard and fast rule on the duration of an Innovation

Partnership, but the time frame chosen should be consistent with the intent to

develop the innovation to a point where it can be subject to a competitive

procurement process.

- The nature of the Innovation Partnership means that intellectual

property will be created as a result and the treatment of this value should be

explicitly dealt with in the contract. A commissioner might take the view that

it is in the spirit of the Innovation Partnership that learning is made open

and transparent, to the benefit of a future competitive process.

- It is important for the commissioner to have full visibility of the

financial costs as well as service outcomes, in order to inform understanding

of value for money in subsequent commissioning.

We believe that the Innovation Partnership method is useful. The term itself can unintentionally mislead. It brings to mind science labs full of bright young things with difficult hair, all writing the code for self-driving cars – rather than a way of rethinking waste collection in Stoke. Nothing could be further from the truth. Innovation Partnerships are simply about creating innovative products, services or works that aren’t currently available to you in the market.

Bates Wells Braithwaite, HCT Group and E3M (2016) ‘The Art of the Possible in Public Procurement’

Voluntary Ex-Ante Notices (VEATs)

The EU guidance is very clear around the importance of not restricting competition, but there are occasions where a provider has developed a unique solution and where they, and they only, have the means to deliver the requirements of the commissioner. In this scenario, the regulations acknowledge there is no point in attempting to create an ‘artificial’ competition, when everyone knows at the start who ought to get the contract, and there is transparency around costs.

In these circumstances, the commissioner may opt to put out a Voluntary Ex-Ante Transparency Notice (VEAT). This (a) notifies the market of the intention to award a contract to a certain provider without competition, and (b) provides for a 10 day (15 day in some circumstances) ‘standstill’ period to allow challenge to that decision. The decision cannot be challenged outside the standstill period.

The VEAT process provides a legal safe haven for authorities, provided they follow the procedure in good faith and with the EU treaty principles in mind (see Section 2.2). However, procurement regulations provide limited guidance on how the VEAT procedure should be applied in practice. Our recommendations are as follows:

- The commissioner should clearly articulate the basis of its decision,

and specify the unique capabilities that it believes the organisation it

intends to appoint holds. You should also be clear on how you know only that

organisation holds the desired capabilities; for example, have you tested the

market to ensure there is no-one else? It is legitimate to give consideration

to the timing of any service (e.g. if there is a particular urgency) and the

likely ability of other providers to develop and mobilise a service on the

required timeframe.

- The testing of whether there are any alternative providers should be

proportionate to the value of the service, and the likelihood that alternative

providers exist. An informed judgement is permissible, provided you can justify

the basis for the judgement.

- The VEAT notice allows 10 -15 days for any organisation to issue a

challenge. We recommend that authorities take active steps to notify any

organisations that it considers may raise an objection in advance of the issue

of that notice. This is outside the scope of the VEAT process as determined

by the legal guidance, but it helps to ensure that the use of this procedure

remains credible and reputable, by reducing the likelihood of a challenge.

- A VEAT process should not be used if there is not yet a defined delivery

model or specification. It is appropriate where an organisation has already

invested in delivery-ready solutions. In circumstances where no provider has a

pre-defined solution, the Innovation Partnership procedure, or a negotiated

process, is more appropriate.

- The authority should also consider how it will agree a contract and

payment terms. We would suggest that terms are agreed in principle before the

VEAT notice is issued. Doing so would create a competitive pressure on the

provider.

Prior Information Notices (PIN)

The Prior Information Notice (PIN) set out in Regulation 28 of the Public Contracts Directive also allows Authorities to use a restricted procedure, but unlike the VEAT process it allows a narrow window for potential bidders to express an interest and then to submit a proposal in a period as short as 10 days.

Like the VEAT procedure, the PIN is being used where a service provider is in a fairly unassailable position, for example the provider may have led the development of a Social Impact Bond and be the direct recipient of a central government development grant such as those available in the Life Chances Fund.

The essential difference between the VEAT and the PIN processes is that a VEAT does not advertise the opportunity to the market prior to the decision to award. Rather, the notice states that a decision has been made and provides a standstill period for organisations to object. A PIN process provides a short window for potential providers to express an interest in participating in the competition.

Co-operation agreements

These should be used where commissioners want to collaborate with other public sector bodies to deliver a contract, rather than to contract to a private or VCSE sector organisation. No competition is required, but there needs to a form of contract that determines the obligations of all parties including the funding arrangements. This procedure was used for the delivery of Family Drug and Alcohol Services in Kent in an agreement between Kent County Council, Medway Council and Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

2.5 Engaging investors (additional detail)

Investors should ideally be subject to competition, and how they are engaged depends on how the service is procured.

Investors can play different roles in relation to the service:

- Provider is the counter-party. The provider holds the outcomes-based contract with the commissioner, and then takes responsibility for finding an investor to share the risk with. The investor gives the provider the money needed to deliver the work up-front; if outcomes are not achieved then the provider doesn’t have to repay (all) this money and the investor loses their capital and receives no return. This structure is simplest and works well if there is only one provider and commissioner – but as commissioner you have limited influence over who the investor is, unless you specify for it in the procurement process.

- Investor is the counter-party. The investor holds the contract with the commissioner. The provider is contracted on a service fee basis by the investor, who shields them from risk. If outcomes are not achieved, the investor will not be paid and stands to lose some or all of their investment and receives no positive return. Sometimes an advisor / intermediary provides performance management of the provider to help assure the investor outcomes will be achieved. This structure can work well when there are multiple commissioners or providers as the investor can act as the ‘central party’ to bring the multiple stakeholders together.

- Advisory or intermediary is the counter-party. This is the same as 2 (investor is the counter-party) but with an advisor or intermediary playing the central role of holding the contract with the commissioner, raising capital from the investor, and contracting the provider. This structure is used either when an advisory/intermediary has led a proposal, or when multiple investors are engaged.

- In a fourth scenario, investors

have ‘co-invested’ alongside the public authority, and have then jointly

procured a provider as partners. Whilst ‘co-investing’ is not subject to

procurement, the choice of ‘co-investor’ should probably still use some form of

competition to ensure good value in the investment terms.

2.6 Three ways to procure a SIB and get value (additional detail)

The reason that you might decide to use outcome-based commissioning vary depending on the challenge you are trying to address.

Sometimes, you may have a clear preference for a particular service or intervention, but you want to reduce the risk of funding it because you are not sure how effective it will be in improving outcomes, or you want to control costs in a different way to usual.

Other times, you may not know what services or interventions will improve outcomes, and so you want to try something new. You may want delivery organisations in the market to come up with the new solution on their own, or you may want to collaborate and share the risk of finding new solutions with outside organisations that have a shared ambition.

The organisation leading the development of the proposition is also important. In some instances, the initiative may come not from commissioners, but from social investors or providers, who have invested in developing a new form of service and are looking for commissioners to work with.

All of these scenarios represent quite different challenges and have different implications for procurement processes. Thinking through these questions will affect the choice of procurement process – a few different options are presented in Chapter 1.5.

2.7 Good practice (additional detail)

A procurement plan

Remember that whatever procurement process you go with, however light-touch, you need to inform the market of your intentions and explain why you are doing it the way you are. Having this clarity will substantially reduce the chances of an effective legal challenge to a procurement decision. We recommend that commissioners set out their intentions in a procurement plan that is open to scrutiny.

The plan might include:

- The rationale for using outcome-based commissioning, if relevant

- How you will engage the market prior to any procurement process, and the

basis on which organisations will be invited to contribute

- The expected involvement of any other types of stakeholders (for

example, social investors), or other commissioners, and one what terms

- How any information that is shared will be treated (intellectual

property)

- What the procurement process will be (restricted or competitive), and

why

- A high level timetable.

Transparency and intellectual property

All outcome based commissioning contracts have some degree of novelty, which means some level of uncertainty in what can be achieved. This means the business case is to some extent a hypothesis, which needs to be proven or disproven through delivery. So, when developing the contract, there is always a balance to strike between using existing evidence of need / intervention effectiveness, and creating new evidence. You might be willing to accept limited evidence at the outset, provided that the evidence is generated during the contract to reduce uncertainty over time. Evidence can be presented or generated by commissioners, by providers, or co-produced.

What all this means is that commissioners and providers need to agree to openly share their intelligence about the need, and evidence around likely effectiveness of the intervention (and continue to share evidence throughout the contract as part of the evaluation process). This is especially true when projects are funded in part through central government funds such as the Life Chances Fund. This openness is a feature of the market, but has implications for the procurement process.

In this early stage in the market, there has been a pioneering spirit that has made the value of knowledge and experience seemingly less important than the opportunity to participate in new contracts. The fact that providers are largely from the voluntary and social sector perhaps makes commercial interest a lesser consideration than the opportunity to create social impact.

However, as the market matures, organisations that have made the investment in developing new know-how might look to create an advantage from it. Consequently, we would recommend that you think about how know-how is dealt with through the whole process, from pre-tender to post-tender evaluation. This means you need to be explicit about what must be shared, and the limitations on what can be kept confidential. You could also use a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) or limited use agreement to give providers comfort around confidential information, if helpful.

One of the lessons from outsourcing generally is that market players keep their know-how secret and avoid transparency – but that this practice is ultimately damaging to the delivery of public services. To counter this, the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) in public service markets provides a market-facing set of principles around standards of transparency. These principles are intended to increase the competitive pressure on providers to show how they will share intelligence for the common good. We would advise that you use these guidelines in your outcome-based commissioning. The quality of collaboration and sharing already achieve in outcomes-based commissioning is acting as a trailblazer for other areas of the contracting market.

You should also make sure that information or evidence that you share at the early stages is, on the equal treatment principle, available to all bidders in any process you run later on.

Agility in delivery

The uncertainty about the likely achievement of impact in outcome-based contracts means there needs to be plenty of room for manoeuvre for a delivery organisation. This should be built into the contract with the service provider, supported by a variation mechanism that enables changes to the terms to be made. And this needs to be considered from the start, at procurement stage: the initial scope set out in the procurement process should anticipate a reasonable level of change in delivery.

Commissioners should expect and encourage the provider to adapt their way of working in response to the evidence being generated from the operation of the contract. The commissioner should similarly be prepared to adapt the way a provider links to other parts of the system of provision – for example, the point of referral into or out of the service.

Commissioners with experience in managing outcome contracts (and social impact bonds in particular) advise taking a pragmatic and flexible attitude, backed by a strong governance structure that expects and manages change. Officers need to be empowered and trusted to make decisions that are in the interests of achieving the end outcomes.